Engine, equipment and emission-control manufacturers will need to keep their lines of communication open for the next several years as regulators focus on their next target in the never-ending push to reduce emissions. Regulators want engine manufacturers to incorporate on-board diagnostic systems into their electronic controls. These systems won't do anything to reduce emissions. Instead they will prevent an increase in emissions by alerting operators when diesel particulate traps, oxidation catalysts and other aftertreatment components begin to fail.

On-board diagnostics has been installed on cars and light-duty vehicles since the early 1990s, but are just now making their way to commercial, diesel-fueled vehicles. In December, the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed regulations requiring the diagnostic systems be on diesel-fueled trucks starting in 2010, and indicated its intent to follow up with similar requirements for off-highway equipment.

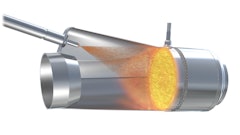

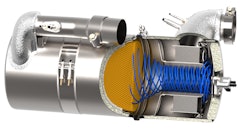

The EPA's proposal is not surprising given the evolution of emission-control strategies. Until now, engineers have relied on engine modifications and electronic controls to drive down emissions. They altered the engine timing, modified the piston and combustion chamber, and added electronic controls and charge-air cooling. After accomplishing virtually all they could in these areas, engineers turned their attention to treating exhaust gases, using technologies such as exhaust gas recirculation (EGR), diesel particulate filters and NOx catalysts. Because these components can fail without compromising engine performance, regulators want to ensure that operators and fleet owners are alerted to any malfunctions that would increase emissions.

"Heavy-duty engines, particularly diesel engines, have very long, useful lives," the EPA's proposal notes. "With age comes deterioration and a tendency toward increasing emissions. [On-board diagnostics] will help to ensure that engines and emission components will be properly maintained and will continue to emit at low emissions levels, even after accumulating hundreds of thousands and even millions of miles."

Engine manufacturers required to develop systems

As with virtually all of the other emission control strategies to date, the ones for meeting the on-board diagnostic requirements will fall on engine manufacturers' shoulders. Truck manufacturers will be required to purchase engines with on-board diagnostics, but engine manufacturers will be required to meet the certification requirements, including manuals for service personnel. They will also be required to provide the specifications equipment manufacturers must follow to install dashboard warning lights.

It won't be any easy task. The broad range of engines and applications make it difficult for manufacturers to design a single approach that can ensure frequent monitoring events on all possible applications. In addition, the thresholds proposed by the EPA will require sensors able to detect slight variations in emissions.

Finally, EPA wants the diagnostic systems to be able to communicate with field testing equipment that state agencies may soon use to test emissions from in-use equipment. Although affordable technology does not yet exist for these field inspections, the EPA wants engineers to monitor developments in this area to ensure their systems will be compatible with whatever testing devices are developed.

Another technology-pushing initiative

Manufacturers will have their hands full as they go about meeting all of these requirements, given the range of systems that will have to be monitored including fuel, exhaust gas recirculation, turbochargers, catalysts, NOx adsorbers and particulate filters, as well as engine misfires and exhaust gases.

"This is a significant issue for the industry and will be a considerable challenge for engine manufacturers," says Joe Suchecki, a spokesman for the Engine Manufacturers Association. "Integrating the sensors with the engine controls will require engineers to revisit the engine operating system and coordinate with equipment manufacturers."

EPA concedes the new standards will be challenging. In its proposal, the agency says it delayed the implementation to give engine and equipment manufacturers time to focus on the technology needed to meet the 2010 emission standards for new on-highway engines.

"The emissions thresholds proposed for highway engines will push (on-board diagnostics) and sensor technology beyond where it is today because of their stringency," the EPA proposal notes. In fact, the EPA has already backed down on some of the threshold standards it first proposed for light-duty trucks (under 14,000 lbs.) after realizing its initial standards were not technically feasible.

Looking ahead at the off-highway market

This challenge will be more pronounced in the off-highway market where engine manufacturers will have to work with hundreds of equipment manufacturers and niche applications where the engine's duty cycle doesn't always lend itself to monitoring. In addition, the off-highway market is much more international than the truck market, which means harmonization with European and other international standards will be crucial.

The EPA did not indicate when it might propose on-board diagnostic requirements for off-highway equipment, but made clear its intentions to do so, noting that off-highway engines are a major source of NOx and particulate matter emissions and are essentially the same as the engines used in heavy-duty highway trucks.

"Having [on-board diagnostic] systems for nonroad diesel engines seems to be a natural progression from the proposed requirements for heavy-duty highway engines," the agency says. "Therefore, we are providing advance notice to the public with the goal of soliciting public comment regarding how we should proceed."

Dave Jensen is a contributing editor from Milwaukee, WI.