In 1919, while agricultural tractor designers were deliberating over the appropriate number of wheels (one, two, three, four?) or style of crawler tracks, a Kansas City company was prepared to say "none of the above."

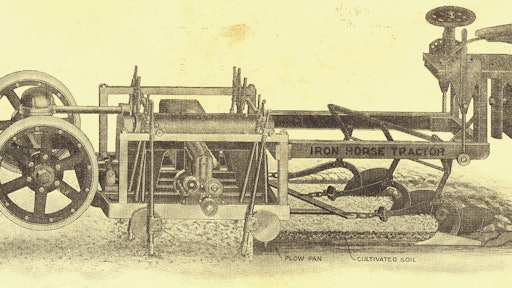

To farmers, the majority of whom were still using equestrian power, the proposed Iron Horse tractor would be familiar in concept yet look like nothing else on the market. The tractor could be driven between fields in a conventional manner: an internal combustion engine propelled the tractor down the road on four wheels. Once in the field the wheels were moved out of the way. The Iron Horse would then stand and propel itself and a mounted plow or other implement by means of 16 "traction legs."

This combination wheel and ungulate tractor was invented by Lou M. Gardiner of San Francisco (later Pittsburgh). He applied for a patent for his farm tractor in 1918 (No. 1,409,165 was granted on March 14, 1922). Gardiner worked for Krupp in Germany before World War I, and had seen walking tractors in Europe. He wrote that his experiments with similar machines had produced the "most powerful tractor ever known for farm work."

In discussing the new tractor Gardiner wasn't afraid of a little hyperbole: "The Iron Horse tractor will be so far superior to all other tractors and will do so many more things, and will be so economical in construction and operation, that there can be no comparison between them, but it will stand absolutely in a class by itself."

At least it could stand. With the traction legs engaged the Iron Horse moved by means of two large crankshafts onto which the legs were attached. When the engine turned the crankshaft through shafts and gears, the hooves moved in a circular pattern with the rear-most feet lifting straight out of the ground as the front feet lowered. Traveling on the Iron Horse must have been slow and undulating.

The left and right leg sections could be operated independently, allowing the tractor to make nearly 90 degree turns at the end of the row. The wheels could be put back into service to get the Iron Horse out of a tough spot — deep, muddy fields would certainly have posed a challenge — or used in addition to the legs. The legs could be angled to facilitate work on hills, providing traction or leveling the tractor frame as it descended or ascended.

A manager of the would-be dealer's parts department would have been happy to discover that the tractor's 16 hooves could be replaced when they wore out or exchanged depending on conditions. Gardiner recommended a "sharp coal chisel" foot to penetrate the soil and break up the subsurface, or a foot "like that of a horse may be used on hard ground and in mowing grass or harvesting grain."

Send money now

The Iron Horse Tractor Co. produced a comprehensive catalog that reads more like a business plan seeking investors in the new company than a sales tool for a new tractor. Perhaps that's all it was. Companies were appearing and disappearing rapidly during this time. Separating con men from serious tractor builders was tough.

But the Iron Horse Tractor Co. was a sound investment, the reader was assured. Of the more than 6 million farms in the United States, most were still using horses. "There are very few of these owners of farms that would not buy a tractor if he could get one that could do all of the things on the farm, in the way of farm work, that the horse could do, and was efficient and reasonable in price, as well as durable," the catalog promised. The Iron Horse was the one that would get them to convert.

Iron Horse did not walk alone

Letters from mechanical engineers and bankers endorsing the Iron Horse seem to indicate a prototype had been built. Most likely it never moved beyond that stage.

That's not to say Gardiner's crazy machine is the only one with a footprint in the history of mobile off-highway equipment. Around this time there were a number of inventors who were trying to solve the challenges of poor road conditions and tough work environments by introducing walking machines; the Official Gazette is peppered with patents for them.

In Germany R. Venzlaff proposed a "striding plate" truck which moved by alternately sliding or lifting two pairs of ski-like runners. In 1924 the editors of Scientific American introduced Fritz Nillson's walking tractor, the Itus, by writing: "In this day of scientific progress it looks as if we are going back to first principles or to imitate nature in many things." Itus pulled itself along with two front legs and two trailing wheels.

Most of these walking machines never got far beyond a mention in an engineering publication. The exception was Oscar Martinson's "Walking Device". Martinson was chief engineer for Monighan Machine Co. of Chicago, which made large draglines. At the time the heavy earthmovers traveled on crawler tracks or via rails. Both methods had their drawbacks.

Martinson mounted a Monighan dragline on a central turntable. When traveling, the machine shifted its weight from the turntable to two large shoes mounted on either side. In this way the heavy dragline could walk to work. At the job site, the digger would sit and rotate on the turntable.

The walking mechanism was patented in 1914 and became part of Monighan's product line. Bucyrus purchased Monighan in 1931, changing the company name to Bucyrus-Monighan. Monighan's walking device continued to see service for many decades afterward in Bucyrus' draglines with a capacity of up to 70 yards.

As for Gardiner's Iron Horse, it never left the gate. Even if he was sincere in wanting to see a walking tractor on every farm, the concept may have been lost in the excitement being generated by other tractor builders.

A good percentage of the industry's attention was on an industrialist in Michigan. Americans had adopted the automobile by the ‘teens, thanks in large part to Henry Ford's Model T. After years of experimenting Ford produced 254 Fordson tractors in Dearborn in 1917. That number multiplied rapidly. By 1920 Ford Motor Co. was the nation's largest tractor manufacturer. Henry Ford's engineers elected to run the Fordson on four wheels: two driving, no feet.

![Cross Control Ag Terminals[1]](https://img.oemoffhighway.com/files/base/acbm/ooh/image/2023/11/CrossControl___Ag_Terminals_1_.6557daeb42a70.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=135&q=70&w=240)