New ultra-low-sulfur diesel is flowing through the nation's pipelines in preparation for the October 15 deadline for on-highway trucks. After investing $8 billion in new technology to create the new environmentally friendly diesel, refineries turned on the spigots June 1 to start the flow of the fuel, which contains 97% less sulfur than the existing on-highway blend.

"So far, the transition has been generally good, but there have been some short-term imbalances," says Al Mannato, fuels issue manager for the American Petroleum Institute.

Although it is intended for on-highway trucks and won't be required for off-highway equipment until 2010, it will likely have a more immediate impact on off-highway markets as terminal operators struggle with the ability to deliver multiple diesel blends. Concerns about contaminating the ultra-low-sulfur fuel by storing it in tanks previously used for fuels with high sulfur contents is also creating some demand and supply glitches.

"There have been some problems in the heartland," says Charlie Drevna, executive vice president of the National Petrochemical & Refiners Assoc. "Because of the drought, irrigation systems are using a lot more diesel. At the same time, terminals are draining their tanks to get ready for the new fuel. It's a timing issue and if the terminal operator doesn't get it right, there can be a supply problem."

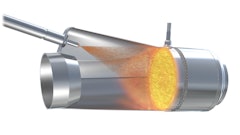

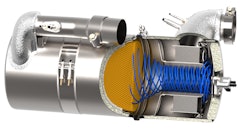

The new diesel, which has a sulfur content of 15 parts per million (compared to the current 500-ppm on-highway fuel), is needed for the emission-reducing technologies that will be standard on 2007 on-highway engines. The catalytic converters that reduce NOx emissions and the diesel particulate filters that trap particulates can be damaged by the gasses and acids generated during the combustion of high-sulfur fuel. And, because sulfur is one of the principal components of particulate emissions, reducing the sulfur content of the fuel also reduces particulate emissions in and of itself.

The real test to occur at the terminal

While refineries and pipelines have reported little difficulty in producing the fuel and at keeping it below 15 ppm as it travels through the nation's underground pipeline network, there are concerns about what will happen at the terminals where end-users purchase their fuel. Many tough decisions will have to be made in order to maintain a sufficient supply of fuel and keep customers happy.

Until next year, when the 500-ppm standard will be implemented for off-highway diesel, pipelines and terminals will be distributing three types of diesel fuel — the unregulated diesel now used in construction and farm equipment (which has a sulfur content in excess of 2,000 ppm); the current 500-ppm on-highway diesel fuel, which will be phased out for on-highway trucks over the coming year; and the new 15-ppm ultra-low-sulfur fuel. Retailers will be forced to balance the need to supply ultra-low-sulfur diesel needed for 2007 trucks with the customers' demand for the less expensive fuels that have higher sulfur contents.

"Every jobber (terminal operator) wants to keep their options open," says Dan Gilligan, president of the Petroleum Marketers Assoc. of America, a trade group for fuel retailers. "We are a business in which every penny counts and the price difference between ultra low and 500 ppm can be significant on any given day, week or month."

Capacity issues are forcing terminal operators to make tough decisions.

"We are already seeing some jobbers discontinuing kerosene and using that tank for the new diesel," says Gilligan, noting the potential for supply challenges later this fall when the demand for kerosene increases.

Hoping there won't be a repeat of 1998

Everyone will be watching the transition to the new fuel with some anxiety. Refineries, engine manufacturers and fleet managers don't want a repeat of what happened in 1998, the last time major diesel fuel changes were made. That transition — to a 500-ppm sulfur content nationwide and a change in fuel aromatics in California — led to a spike in prices and a rash of gasket leaks and fuel pump failures.

"We don't expect any problems, but people should pay attention, especially to their fuel filters which may need to be changed once or twice out of cycle," Mannato says. That's because the new fuel is expected to act like a solvent in the fuel system, breaking up sediment and other deposits that could prematurely clog filters. It is expected to be a temporary issue and no one is sure how significant it will be.

The new fuel will be more expensive — both in unit price and operating cost. It will cost at least a nickel more than 500-ppm blends, provided there are no supply disruptions, and is expected to increase fuel consumption by up to 2%. Consumption will even be greater on 2007 trucks because the new emission-reduction technologies require additional fuel to be burned when the engine is running at low speeds.

It remains to be seen how successfully the transition to ultra-low-sulfur fuel will be. As of August, the new fuel already represented half of all the diesel fuel being produced by refineries, but it hasn't fully made its way into trucks and other equipment. Nor do we know how well refineries, pipelines and terminal operators will be able to maintain supply and keep the fuel from being contaminated by other fuels with higher sulfur contents.

The farm and construction markets are fortunate in that they can learn from the trials and errors that will occur in the on-highway transition. However, that doesn't mean they won't be impacted. Any major glitches anywhere in the production and distribution process will quickly spill over into the off-highway market.

"It has been a very expensive and very challenging transition and we are just at the beginning of this," says Drevna. "We're running at full bore. All it takes is one hydrotreater to go out and we will have a supply disruption."

Dave Jensen is a contributing editor based in Milwaukee, WI.