The transmission is a complicated system, interacting with the engine, the hydraulics, the electronics and interfacing directly with the operator and his controls. Engineering teams designing the transmission system must work with several system experts to optimize a transmission’s communication and seamless cooperation with the rest of the vehicle to create the most effective technology possible.

According to CVT Corp.’s founder and CEO Daniel Girard, the control of the clutch is paramount to the efficient operation of the vehicle by the operator. “The biggest integration work [on a continuously variable transmission system] is done by the electronic control unit (ECU) and software engineers. What makes a product good or bad is how you control the components to behave as a whole and not as individual components. Working with other component system experts to create a fully optimized system is completely necessary.”

The goal of a transmission system, and a key focus with continuously variable transmissions (CVTs), has been to enhance “the big three” features: increase fuel efficiency, reduce emissions and improve overall vehicle performance. “The functionality of the transmission is to become the energy management device in the system,” says Bill Klehm, Chairman and CEO of Fallbrook Technologies (Fallbrook), San Diego, CA.

The OEM – A Split Power System

Caterpillar Inc., Peoria, IL, recently announced its 966K XE wheel loader equipped with an advanced powertrain system (a term coined by the company to refer to its internally designed and manufactured CVT). The transmission system from Cat helps the wheel loader to deliver a fuel efficiency improvement of up to 25% to equipment owners.

The advanced powertrain was created by Caterpillar’s Advanced Systems and Controls division, led by Tony Marcott, CVT Engineering Manager. “Our business unit provides a lot of components beyond the powertrain including cabs, hydraulics and electronics, so we’re constantly focused on ways to provide new value to customers of our machine groups. The first machine group to step up was the wheel loaders with the value proposition for fuel and productivity improvements which translates directly into reducing life cycle costs for the whole machine,” explains Marcott.

The transmission system was worked on for several years, with some patents going back 20 years when Caterpillar was first experimenting with the technology. The long development time demonstrates the engineering team’s commitment to move the technology through prototype and experimental phases all the way to final production and system integration to the final machine. It is not often that systems are designed from scratch and launched to market, as most new products are modifications to existing components. “People like to pick up proven techniques and turn them into a new solution,” agrees Marcott. “We actually had a couple of inventions in mind for a new transmission solution.”

The economic downturn found the engineering team for the Advanced Systems and Controls division fighting to keep the research and development funding to continue the project. “2008 threw us a curve ball and we had to do a strategic shift in the program to save it. In a sense, we had to almost redesign the whole transmission. When we made that decision in 2009, if you look at what we were able to accomplish within three years, that’s fast, especially including the time Caterpillar took to test and validate its machine,” says Marcott.

Cat’s CVT is a split-power configuration, and is not technically classified as a hydrostatic transmission, though it does use a pump and motor much like other equipment manufacturers are implementing in parallel with mechanical transmissions. The hydraulic pump and motor (variator unit) allow for the smooth continuous gear ratio changes between the engine speed and the machine speed. The motor reduces the heat load generated by the drivetrain during functions like digging and climbing with a heavy load while providing the gear ratio flexibility to allow the engine to run at its most efficient operating speed. Power through the variator unit and parallel mechanical gear path is combined through a series of planetary gear sets to maximize the transmission’s efficiency over a wider range of operating conditions.

Utilizing Cat’s C9.3 ACERT Stage IIIB engine with 290 peak net horsepower (220 kW) rating, the transmission system operates at extremely low engine speeds providing optimal productivity and burning less fuel, thus reducing soot buildup for longer regeneration intervals, cutting fuel use even further.

Leveraging the internal expertise of several sub-component systems divisions such as hydraulics, electronics and engine capabilities within the Caterpillar walls, the Advanced Systems and Controls division was able to create an optimized powertrain system. “A transmission gets power from the engine, electronic signals from the machine’s electronics and drives implement pumps in the hydraulic system, so it has to cooperate to an unbelievable level,” says Marcott. One manager described the split transmission system as the “most integrated system on a machine in his 30 years of experience at Caterpillar.”

The 966K XE received positive customer feedback during its pilot program on the smooth ride and simplified operation. System transparency to the operator is a common goal with the rapidity at which technology is advancing. Additional features like full automatic or shift-free deceleration add significant comfort and value to operators who are increasingly looking for automotive industry luxuries and interaction with equipment. An operator has the ability to control the machine’s maximum ground speed through virtual gears for flexibility during various machine functions. During deceleration, energy can be recovered to power implements or the cooling fan.

“With advanced powertrain, you don’t have to pay attention to shifting anymore. It’s basically an automatic transmission,” says Marcott. The operating interface is able to be reduced to just two pedals, and any reduction in operation complexity allows the driver to concentrate on his other responsibilities to increase overall productivity and awareness of the outside environment.

Caterpillar is continuing to develop solutions for other applications, as split-power CVTs are not a solution for every machine or duty cycle. “Split-power CVTs have limits in maximum horsepower due to scalability of the hydraulics and mechanical elements of the system. They also don’t make a lot of sense on smaller, lower horsepower machines because of duty cycle. There are challenges in the economics in the lower horsepower range, and challenges with the technology capabilities for higher horsepower machines,” Marcott says. “The advanced powertrain works well in the middle horsepower range, and it has plenty of opportunities within it.”

The Strategic Alliance – A Continuously Variable Planetary (CVP) System

On September 13, 2012, Allison Transmission Holdings Inc., Indianapolis, IN; Dana Holding Corp., Maumee, OH; and Fallbrook announced the formation of a strategic relationship to develop, manufacture and commercialize high-efficiency transmissions for commercial vehicles and off-highway equipment. Through the agreement, Dana and Allison gain exclusive rights from Fallbrook to utilize its NuVinci continuously variable planetary (CVP) transmission system to develop and commercialize transmissions for their specific end-user markets.

“The two companies have significantly different approaches to the marketplace. We think our alliance with Allison and Dana addresses what we saw as a lack of overlap in how the market is addressed with technology delivery,” says Fallbrook CEO Klehm. There is also a signed letter of intent between Dana and Allison to explore a strategic alliance through which Dana would exclusively manufacture transmission components with NuVinci CVP technology for Allison.

George Constand, Chief Technology Officer at Dana, sees NuVinci’s CVT technology as a unique and potentially disruptive technology in the industry. “From a fuel efficiency standpoint, Dana sees an 8% fuel efficiency savings to owners. The technology comes in a smaller package than traditional transmission arrangements at a significantly lower weight,” he says. The NuVinci system is a potential replacement for torque converter arrangement and powershift-type transmissions. “We also see the ability to replace the hydraulic pumps and motors in a hydrostatic unit,” says Constand.

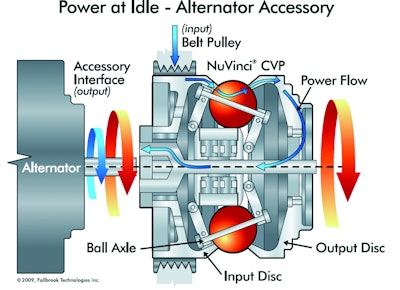

Instead of the traditional gear and clutch mechanisms found in conventional transmissions, a NuVinci transmission from Fallbrook utilizes a set of rotating spheres arranged around a central (sun) gear that transfers torque between two rings. The NuVinci CVP technology is a traction-based CVT that is fully scalable from a bicycle to an off-road piece of equipment in Allison and Dana’s end markets. NuVinci’s unique planetary kinematics enables the system to act as both a CVT and infinitely variable transmission (IVT) without needing additional mechanical power paths. Most CVTs only go forward and require an extra set of gears to go in reverse, but the NuVinci transmission does not require the extra gearing.

“Everyone is trying to match the creation of energy with the use of energy; that is how you maximize efficiency,” says Klehm. “An engine or other power source is a series of explosions, and the user needs those explosions to be managed artfully to do the most work possible with the least amount of waste.”

Fallbrook is currently spending time with both Allison and Dana to design and deliver initial designs for commercialization to their individual applications. On its third-generation transmission technology, Fallbrook plans to continue to expand its knowledge of the technology through working with Allison and Dana, as well as a more recent development agreement with Team Industries, a leader in belt CVTs for small off-road work vehicles.

Fallbrook seeks to enable the simplification of technology by providing the intelligence inside the mechanical system to allow vehicle designers to rethink the way they’ve been designing their vehicle systems. “There is a technology wave coming and it’s a simplified driveline that provides value at affordable costs,” he continues. “The next step for us is to move into the accessories and reduce parasitic losses in systems such as the alternator or air conditioning pump. We also have an effort in transportation variable supercharging.”

“I fundamentally believe the systems that are going to survive into the future are simple systems with more functionality at less cost. So, if you’re going to design a hybrid drive, the drive better have more functionality and cost less than its predecessor. ‘Clean technology’ is currently, in my opinion, an industry misnomer to make money,” says Klehm.

“We’re going to continue to move forward and manufacture systems for some applications ourselves, others we will choose to leverage through a joint venture, and other opportunities through licensing such as with Allison and Dana,” Klehm says. “We’ve raised over $100 million and developed prototypes and models to be able to explore the edges of the transmission technology so we can commercialize it with our partners, and then take all of those variations and patent them.”

The Manufacturer – A Flexible Mechanical System

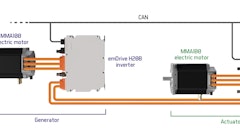

As if the name of CVT Corp. necessitated further explanation of the company’s primary capability, the Quebec, Canada-based continuously variable transmission manufacturer focuses on developing high efficiency mechanical systems. “We don’t have to transform the power from hydraulic back into mechanical, allowing for higher efficiency in our system,” says Girard. CVT Corp.’s system has over 200,000 hours of testing logged, and has generator applications up to 400 hp.

The company began as a CVT manufacturer for stationary generator sets which were running at fixed speeds regardless of load, and later realized the opportunity for mobile equipment applications. “The technology naturally migrated into a New Holland tractor because my father was a dealer, and it was a very successful integration. We currently work with most of the leading OEMs in the market for various applications such as tractor drivetrains, fan drive applications and combine header drives,” Girard says.

Girard sees many CVTs with preprogrammed fixed speeds replicating the behavior of a dual clutch transmission. “We can program our CVT to behave as a dual clutch, then change the interface for true CVT behavior, or we could add a couple more mechanical parts and replicate a full IVT. The benefit to the OEM is to have one single platform to cover the range from powershift dual clutch transmission to CVT to even IVT configurations,” says Girard.

Changing the habits of the end user is a risk not worth taking considering the amount of time and cost associated with a technology’s development, so the company developed its system under the pretense that its functionality remains seamless and transparent to the operator. The filters and oil capacity were sized to ensure the transmission outlasts the oil, and Girard states that there is a generator running on 12,000 hours with the same oil.

The most important thing for a transmission is its ability to effectively communicate with the engine. CVT Corp. specializes in the CVT cartridge, the portion inside the transmission that ensures the ratio variation. The largest level of integration is done through the ECU and software to translate vehicle symptoms affecting the transmission’s operation.

CVT Corp. developed a standard transmission that applies to several applications, both stationary and mobile. The goal was to mass produce a transmission to reduce the cost for customers. “What we do is take various cartridge options depending on the power range of the application, load factor and service factor and we rate the transmission differently just like an engine manufacturer would do,” explains Girard.

“We try to keep as many internal components as standard as possible. We use standard speed and temperature sensors and keep our transmission as affordable as we can. In the basic version of the transmission, there are no electronics at all and it’s controlled entirely through mechanical linkage. Dress it up with a few sensors and our transmission can offer many features of higher end systems with the simplicity of a standard system. It is well positioned for emerging markets that are going to higher horsepower but with basic support networks,” Girard says.

The standard platform design of the transmission allows CVT Corp. to customize the system to each OEM’s specific design parameters. Girard believes that within 10 years, the mechanical CVT will replace powershift transmission, but the system needs to have gains in power density to technically increase efficiency. “If a hydraulic transmission could be produced at a lower cost, there would be no need for mechanical CVTs. That’s the limitations of transmissions, and we came to market to solve that problem.”

The Development – A Universal Transmission System

VMT (Vernier Moon Torque) Technologies LLC, Provo, UT, does not manufacture, nor does it plan to manufacture its universal transmission technology. The company is seeking OEMs in different markets to partner with and commercialize its system for each application. “The reason we call our system the Universal Transmission is because it has many different applications in many different industries,” explains Mike Agrelius, Sales Director at VMT.

The mechanical, positively engaged IVT requires no clutch or torque converter and is constantly engaged. It does not use friction to change gears. The transmission works by expanding or reducing the diameter of a “moon gear” that drives the chain to change the gear ratio. Since the system does not rely on friction, VMT claims it can handle more than 1 million Nm of torque. Fuel consumption is estimated to be reduced by as much as 30% in some applications.

“We’re in negotiations for a physical prototype being developed in the agricultural market and the trucking industry, as well as interest for a wind power application,” says Agrelius. The technology’s proprietary operating system algorithms have all been validated in virtual prototype models, as well as a physical test bench to verify the principles.

With mounting fuel efficiency standards and expectations, CVTs provide major reductions in fuel usage because the engine is never disconnected from the load to always maintain inertia. In a traditional CVT, the sheaves would push together to change gears, but with VMT’s version the two sheaves are only there to help guide the ratios of the system. VMT uses a proprietary chain design instead of a belt, and the chain is wrapped around the gears for the positive engagement with the sheaves. “We’ve solved the common partial tooth integer problem with our proprietary coding, making the system function completely harmoniously,” Agrelius says.

“There is a great potential for the heavy-duty off-road market to benefit from this technology, especially with the significant amount of shifting that can occur for simple turns or uphill angles,” he continues. “That’s very ineffective to be shifting that much. With our system, an owner is going to save a lot of money in fuel costs.”

Infinite possibilities

Many of the CVTs mention potential to enhance hybrid vehicles. As VMT explains it, a lot of battery power is used up during the start and stop of a vehicle, as well as during gear shifting, so there could be an opportunity to extend battery life of an electric vehicle. “In electric and hybrid vehicles, the Universal Transmission could replace the vehicle’s ECU,” says Agrelius.

Fallbrook sees a possible place for energy savings in ultracapacitors by splitting the energy draw across multiple electric motors across the transmission with an internal combustion motor. “We will enable brand new, less complicated hybrid drive systems that are envisioned in the marketplace with our flexible technology,” says Klehm.

The future possibilities of the continuously variable transmission system and its various versions demonstrate the present and future potential to harness significant fuel savings and reduce emissions while improving overall vehicle performance. As the technology becomes more robust and widely accepted and implemented, its possibilities are quite possibly limitless…or rather, infinite.