With the new year came new U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) emission regulations for small engines. The new EPA “Phase 3” emission regulations impact OEMs, as well as distributors, dealers, repair shops, rental centers and end users. Last year, all small spark-ignition engines greater than 225cc were impacted. This year, the regulations include all engines smaller than 225cc. By the next year, all gasoline-powered equipment will need to be certified by the EPA.

All of these requirements are rolled into Title 40 of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations under Sections 40 CFR 1054 and 40 CFR 1060.

What it’s about

To really understand how this affects consumers, it’s necessary to first take a look at what the regulations impact: evaporative emissions. When liquid gasoline turns into a vapor, which happens when it’s warmed, evaporative emissions result.

The California Air Resources Board (CARB) has regulated evaporative emissions from equipment powered by small gas engines for several years, although most agricultural and construction equipment has been exempt. These regulations went nationwide via the EPA in 2011 and expanded in 2012. According to the EPA, small engines will emit about one-third fewer hydrocarbons under the new standards.

The regulations aim to control running losses and permeation losses from fuel systems. Many people are surprised to learn just how much fuel vapor passes through the walls of untreated plastic fuel containers alone. Permeation is just one way in which fuel vapors are emitted, though. Evaporative emissions occur when an engine is running as well as through diurnal loss, when the engine isn’t running, due to daily temperature changes.

Each equipment builder must control evaporative emissions from fuel systems and get equipment certified with the EPA. This trickles down to the end user, who needs to be aware of how the changes accompanying the regulations effect the product they are using and servicing.

What it looks like

Some manufacturers have been ahead of the game in improving products to meet the standards. Those manufacturers employ a number of methods to control evaporative emissions, from special hoses to fuel caps on sealed fuel tanks to carbon canisters and vapor control valves. Here’s a breakdown of what that looks like inside any new equipment a consumer may purchase.

Hoses that come in direct contact with liquid gasoline must now be special low-permeation fuel hoses, which are manufactured specifically to limit the amount of fuel vapors that permeate through the hose wall. The hoses need to be kept free of kinks and obstructions to ensure good working order.

Under the changes, most fuel systems are now sealed, and vented fuel caps have been primarily replaced with sealed caps to prevent evaporative emissions. When a sealed cap is used, there will be different hose connections. In addition to the normal fuel hose connection at the bottom of the tank, there also will be a connection for the vapor hose at either the top or bottom of the tank.

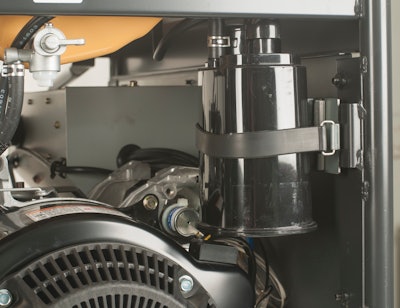

There’s one exception to the sealed fuel cap on some small engines, though. In those cases, the fuel cap self-vents through a carbon canister. The canisters come in different shapes and sizes and may be anywhere on the equipment, which makes it difficult to identify. The best method for locating a carbon canister is to first look for the spot where the vapor hose connects to the engine intake system, and then work backward toward the fuel tank. If the vapor hose connects directly to the tank, there will be no carbon canister. If the vapor hose appears to first go to a box, that is most likely the canister.

The carbon canister works to absorb diurnal vapors. When the engine runs, an intake vacuum draws any vapor from the tank into the engine, where it is burned. After the engine is shut off, vapors continue to be emitted into the atmosphere due to temperature changes throughout the day. The carbon canister absorbs those vapors, and when the engine is started again, the engine intake vacuum will draw in fresh air through the carbon canister’s vent port and thus purge the stored vapors.

Some engine manufacturers also are incorporating optional vapor control valves in new systems. These devices prevent liquid fuel from getting into the vapor system. Originally developed to prevent fuel leakage during rollover accidents, these also might be referred to as “rollover valves.”

What’s required now

Beyond making the adaptations to the new systems to limit evaporative emissions, OEMs must complete several steps to ensure adherence to the EPA’s regulations. This includes registering through the Verify system, labeling engines according to the standards, and providing emissions-related warranties. This all effects the look of new equipment, as well as adding new warranty guidelines of which consumers should be aware. A basic understanding ensures generators and other small-engine-driven equipment will last for years to come.

The EPA’s Verify information system collects data on emissions and fuel economy compliance for all sizes of engines. Each manufacturer must register with the EPA and apply for evaporative certification for its equipment through Verify. Manufacturers cannot sell equipment until obtaining the certificate through Verify, so rest assured that any new equipment purchased will meet the new standards.

Under the new regulations, manufacturers also will need to place an approved evaporative emissions label on the equipment. This label must be permanently affixed or engraved on the engine and will include the heading “EMISSION CONTROL INFORMATION.” It will be followed by the manufacturer’s corporate name and trademark, the EPA’s standardized designation for the emission family and the date of manufacture. The EPA also requires that the label include the emissions compliance period, in hours, over which the engine exhaust emissions system was tested. A statement certifying that the engine meets exhaust emission regulations also must be included. While more information can be added, the above is what’s required on any small engine-operated equipment now manufactured and sold in the United States, so expect to see it on any new purchases.

Each piece of new equipment also must come with an approved evaporative emissions warranty statement. Under this requirement, consumers purchasing the equipment (along with each subsequent buyer) will know that the engine, along with all of the parts of its emissions control system, meets two conditions. First, at the time of sale the engine is designed, built and equipped to meet EPA regulations and, second, that there are no defects in the workmanship or materials that would keep the engine from meeting emissions standards.

The EPA requires a minimum two-year emission-related warranty, although exceptions are made for some handheld engines used in more intense, seasonal service. The warranty covers any component that, should it fail, would increase the engine’s emissions of a regulated pollutant. Manufacturers will spell out all of the warranty details in the owner’s manual and provide a toll-free phone number and email address so that consumers can quickly file a warranty claim and have authorized repairs made so that they are not without their tools for long.

What can’t be done

With these new standards in place, it’s no surprise that some things now can’t or shouldn’t be done with generators and other small-engine equipment.

First and foremost, don’t tamper or attempt to modify engines designed to meet EPA standards. Not only is it illegal and comes with civil penalties, but it can cause a host of problems. For example, removing an engine’s vapor control valves presents a fire hazard and can cause liquid fuel in the vapor system to severely damage the carbon canister.

Knowingly disabling an emissions control system component, from tweaking the fuel or exhaust system to altering the engine’s performance, will violate the EPA regulations. Installing a part that differs from that originally on an engine that meets EPA standards also may bring penalties for tampering.

Even without EPA penalties, it would be foolish to attempt to make changes. This equipment has been manufactured to be the best for not only the environment, but the long haul. With basic maintenance, it’ll run long into the future and provide a great return on investment as the latest technology is powering the generator, pump or other piece of equipment. Normal maintenance (replacing air filters and spark plugs) and routine servicing such as rebuilding carburetors, adjusting the fuel mixture within the allowable range or replacing jets for high altitude operation are still perfectly acceptable.

Don’t take these new changes too far, though. Trying to place a new sealed fuel cap on an older pre-EPA fuel system won’t help the environment. Rather, it will cause fuel starvation because the engine won’t be able to vent properly. Doing the opposite—placing a vented cap on a new EPA-certified fuel system—will cause even bigger problems. The engine will experience uncontrolled emissions losses, plus it will be in violation of EPA regulations. Keeping things as the manufacturer intended will ensure the equipment runs to the best of its ability, meaning minimal maintenance and expense.

Finally, don’t try to replace a carbon canister cap with a standard cap. Equipment that meets the so-called “50 state” product distribution guidelines — meaning it meets CARB standards and can be sold in California — may have a special fuel cap with a self-venting carbon canister built in. Replacing these caps with a standard cap, or replacing a sealed cap with a canister cap, violates EPA regulations.

What can be done

From personal use to operating a small business, there are a few steps to help make this transition a little easier. The first is education, and the above information should have that goal almost completely covered.

The manufacturer should provide much of the rest, such as a list of any critical emissions-related maintenance. This might include any adjustment, repair, replacement or cleaning of the components used to control emissions. Other recommended maintenance and the corresponding schedules also will come from each manufacturer. Following those guidelines will ensure the equipment works like new every time and lasts for years to come, bringing the best return on the initial investment.

When a generator, for example, requires a replacement part, it’s still acceptable to use new or rebuilt parts made by independent parts manufacturers. It’s vital, however, to ensure those parts meet the engine’s original specifications. Using an aftermarket part that doesn’t conform to the original part’s design and function can void the emissions-related warranty. That just spells trouble down the road. Following basic manufacturer guidelines and replacing parts, when needed, with like parts will ensure the greatest return on investment as the generator powers year after year with ease.

In terms of the warranty, each new engine sold will offer at least two years of warranty coverage on its emissions components. The warranty covers the repair of emissions-control-related parts that are found to be defective within the first couple of years of service. Each manufacturer will include a phone number and email address in the operator’s manual to ensure quick, easy access to filing a warranty claim. Ensure none of these parts are tampered with since that may void the warranty, but know that things will get repaired quickly when needed.

Any piece of equipment that has survived the long haul and predates EPA emissions standards won’t need to be altered to meet the new standards. It should continue to be regularly maintained as recommended by the manufacturer to ensure its continued long life.

Follow a manufacturer’s maintenance schedule closely for new equipment, as well. Generators and other small-engine equipment will last even longer than anticipated when routine care and maintenance are performed according to the operator’s manual. Be sure to seek out qualified engine technicians for assistance on more advanced tasks to ensure the engine will continue to meet EPA standards and run smoothly into the future.

More than anything, know that new small-engine products will be the best on the market. Besides the penalties and hazards that come with tampering with emissions-control components, it’s just ridiculous to do so. While the EPA estimates that small-engine equipment will cost about $5 to $7 more under the new regulations, the agency also asserts that durability will improve and fuel efficiency will increase with the changes. In short, the small-engine products purchased today may cost a bit more up front, but these tools are a better value in the long run for not only the consumer, but the environment.