The story of the heavy equipment industry is one of fast inversions and changes—changes that many OEMs who have diversified into the Chinese market have not been able to keep up with. It is not for a lack of insight, planning or preparation to infiltrate China. Often it comes down to an OEM’s unwillingness to relinquish its corporate perception, the very value proposition it has spent years and millions of dollars developing and promoting. Unfortunately, when in a different region such as China, if the market does not recognize the value proposition an OEM adheres to, there will be a self-imposed block between the product and the consumer it is trying to reach.

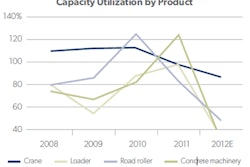

Global demand for construction equipment is expected to decrease 16.2% in 2012*, mostly driven by China, then slowly recover at about a 0.4% growth rate over the next five years. Growth is anticipated due to continued urbanization and development in emerging markets driven by significant population growth (with global population estimated to increase by 1.3 billion people by 2030). The demand in China strongly correlates to its local GDP and remains extremely dependent on government investments in infrastructure, which can prove challenging for OEMs establishing and managing volume changes and deploying global platforms.

China did recently announce more investment in its infrastructure. According to The Financial Times Ltd., the massive infrastructure spending package totals approximately $158 billion US and is set to help support economic growth. “The money will be rolled out over several years…the government has not described the investments as a stimulus package, but the announcements nevertheless fuelled renewed optimism about China’s prospects,” Simon Rabinovitch writes on ft.com. The investment includes 60 projects in the areas of subway and light rail systems, road building, ports and airport runways, warehouses and sewage treatment plants.

A major factor OEMs take into consideration when evaluating the Chinese market and economy is its recent GDP downtrend. The first couple of months of 2012, China reported around 8.3% GDP growth, and recently the country’s GDP has been estimated at closer to 7.7%. “That’s [a] massive … macroeconomic assumption that … OEMs are taking into consideration as … they size and see the market evolving,” Francesco Barosi, managing director at AlixPartners and co-lead of the firm’s global Heavy Equipment Practice, says. “Still, it is very clear that the management teams at OEMs are continuing to be bullish. The fundamentals of urbanization and excavation percentage, and the projected need for infrastructure, are all key assumptions [that managements] still believe are in China.”

“If you look at the end of 2011, the major OEMs were announcing impressive capacity increases, going for instance, up to 370,000 units in the excavator market just for China,” says Barosi. “These are projects that would normally take six to 12 months to complete, and by January of 2012, OEMs were already wondering what to do with all of the accumulated inventory in China.”

Barosi had just returned from several trips to China to meet with large players in the construction equipment industry (lenders, lessors, dealers, buyers and manufacturers). The conversation has evolved between AlixPartners and OEMs to, “How do you adapt to such fast-paced trends and correctly size the market so you don’t overinvest and create excess capacity today, yet are ready to meet the expected growth of tomorrow?” BRIC markets (Brazil, Russia, India and China) overall are expected to increase infrastructure investments by $220 billion annually, making it imperative that OEMs find ways to position themselves appropriately to benefit from this anticipated emerging-market momentum.

“Ten to 15 years ago, the economy was going through easily mapped cycles consisting of a couple of years. Now we’re seeing countries like China with cycles of only a few months. How does an OEM react to that?” Barosi asks.

OEMs will face challenges when it comes to optimizing their investments in emerging markets while still meeting regional equipment-user requirements. “The marketplace has turned into a gold rush,” Barosi says. “Every macro-economic indicator says if you’re not already in a developing market like China, you’re missing out on an opportunity.” OEMs have two options ultimately: They can rush to the emerging market and invest in market discovery (with an established timeline as to how long an investigation will be warranted before results are necessary), or they can wait until they have the “right” product at the “right” price point with the “right” branding message, but risk waiting too long to capitalize on a market while it’s in a growth period.

Selling the value proposition

Developed market-based value concepts such as Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) and Total Lifecycle Management (TLM) are only partially considered by typical customers in emerging markets such as China as they consider competitive alternatives and make purchase decisions. In particular, there is little focus on productivity elements of TCO such as extraction efficiency and the machine/operator interface., meaning there is little willingness to pay for “subtle” productivity enhancements such as reduced load-cycle times or greater ground engagement.

In addition, even as markets such as China evolve toward a more complete application of TCO, their quantitative models will most likely have different weightings than in developed markets. Operator costs, for example, are much less, so any design enhancements that reduce operator hours would be worth less than in a developed market.

OEMs, however, are still attempting to sell a high-end value proposition in developing markets – plus they also have a weaker overall economic climate working against them. The “long-term investment approach” is not feasible currently; instead, customers want to spend less now, weather the economic downturn until the economy picks up and then buy a more expensive piece of equipment. “People are strapped for cash and want to be more financially flexible. They’ll go for the smaller machine that costs less instead of adhering to their same value proposition as they would during an investment-charged economic climate. For now, people are okay with a machine that is good, not great. They don’t need the ‘Ferrari’ of the off-road industry,” says Barosi.

China is still at a “Stage 1” level of capability. A Stage 1/Stage 2 strategy refers to a company establishing two (or more) brands based on differing levels of support, technology and service benefits. Currently, Chinese OEMs have positioned themselves mostly as mid-level brands with broad distribution, a low price point and few advanced technologies. With this positioning, Chinese manufacturers have also focused on exports to Brazil, Africa and the Middle East, where product and support expectations are similar to those in China. Conversely, European and North American markets, with higher content (add-ons, technology enhancements, etc.) and prices are still dominated by non-Chinese players.

Globally, Chinese manufacturers now account for 55% of sales volume—up from 30% in 2007*. At the same time, the Chinese market remains extremely volatile and fragmented, with no single Chinese OEM capturing more than 10% of market share. Though their reach is growing, Chinese manufacturers have continued to struggle to penetrate more mature markets due to product reliability issues, dealer distribution and aftermarket support. The facility SANY recently established in Peachtree City, GA is a significant step to offset some of these disadvantages in the US market.

Says Barosi: “One of the ‘a-ha’ moments from my conversations [with Asian OEMs] was, ‘How does an OEM position its value proposition in the right way and in the right context at a moment in time?’ Is the market ready to accept your equipment as is, or are you only selling 20 units per year, for example, of a high-end vehicle that is not in demand while the majority of your sales come from smaller equipment?”

Optimizing margins and establishing global platforms

Companies have oftentimes tailored products to individual “mini-markets” – e.g., unique equipment designs for corn versus soy harvesters in the agricultural equipment industry. This has driven market segmentation as to how companies develop products. However, though solutions within company product lines may be great, overall industry solutions are often very similar— e.g., wheel loader from Company A versus a comparable wheel loader from Company B. “People will tell us that some products are very similar, with the ‘paint and decal’ the only significant difference,” Barosi says.

The “old mentality” of equipment coverage equates more product lines with a broader range of customers served, he says. Demand can be viewed from a less polarized, or segmented, perspective, however. Focusing product lines into smaller ranges can still address the majority of customer demands.

“Incumbents [OEMs] are trending toward upscale equipment, because bigger equipment has a greater profit margin with sales and service. Those same OEMs should be optimizing the margins in their middle and smaller equipment sizes. That’s how an OEM adjusts to a changing environment, by having a more balanced selling and manufacturing approach…,” he continues.

“If an OEM wants to truly exploit the benefits of a global platform, it has to break away from the old mentality that more content on a vehicle equals more [profit]. That mentality has driven product differentiation led by marketing organizations, that get their information from dealers, who are hearing this from their end-user customers. High-tech options seen in cars, such as touch-screen interactivity, are being brought into the off-road marketplace, and operators will ask a dealer for that option, but then that message turns into, ‘I can’t sell equipment without these additional [features],’ and the cycle continues.”

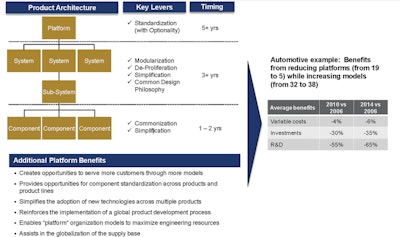

The global standardization movement says the fundamentals of vehicle design will remain constant regardless of the region it will function within, but depending on the level of sophistication requested, layers of benefit-delivering technologies and solutions are added in the distribution region. It represents a more modular vehicle design, allowing OEMs to decrease the number of vehicle models, reduce parts inventory, shorten manufacturing complexity and time to market, thus lower costs -- all while allowing the OEM to be more flexible to address rapid changes in regional demand that our fast-paced global economy is experiencing.

“Platforms are established through aggregating components and sub-components into groupings ordered in a logical and hierarchical architecture. At that point, an OEM can determine which components can be sourced globally for all-wheel loaders, for example, such as a simple windshield wiper. You can go [for instance] from 15 suppliers and 62 different part numbers to one supplier and only seven part numbers. That’s how you take out waste and redundancies,” explains Barosi. “That’s how you exploit a platform to optimize design, and have significant savings.”

Platforms can also simplify the adoption of new technology across multiple product offerings, and aid in the efficient organization of engineering resources. Through an open-minded approach, an OEM can reevaluate product counts, find platform commonalities and gain market perspectives specific to their regions of interest.

Global platform strategy must be tailored to the off-road industry, and to the volume and life cycle of its equipment, not be “copied and pasted” from an industry such as aerospace or automotive. The industry’s strong heritage should be leveraged as a positive, across geographies, says Barosi. “There is value that can offset some of the competitive pressures that established OEMs are facing from newcomers…. OEMs need to look internally to find ways to offset business-model inefficiencies, like product cost and design [inefficiencies in] the core skeleton of the machine.”

“Established OEMs simply cannot afford to let their value propositions, costs or flexibility get out of line,” he continues. “Our research shows that Chinese customers perceive Chinese offerings to be winning on the fronts of price and service, as being competitive on fuel efficiency and as being ‘close’ on reliability. As Chinese OEMs continue to get better product quality and reliability, it will be increasingly harder to beat them in China and to defend against them at home in the developed markets they are coming to.”

*Data provided by AlixPartners

AlixPartners LLP is a global business-advisory firm offering comprehensive services in four major areas: enterprise improvement, turnaround and restructuring, financial-advisory services and information-management services. The firm has offices around the world, and can be found on the Web at www.alixpartners.com. Francesco Barosi focuses on corporate restructuring and performance improvement, serving as advisor to both financial and industrial players. He focuses on operational management and business due diligence to deliver operational improvements aligned with company goals for a wide-range of industries. He can be contacted at [email protected].