An open-bowl scraper can only do so much to load itself because of the tension between resistance on the cutting edge of the material being loaded, the strength and efficiency of the scraper’s design and construction, and the tractive effort being applied to the scraper by machines or animals. It didn’t take very long after the introduction of large scrapers suitable for use behind crawler tractors for contractors to realize the advantage of using a second tractor to assist in loading the scraper.

The idea originated before mechanization, when additional stock could be hitched to a scraper to assist the team pulling it. Called snatch loading, this idea was carried forward into the modern scraper era in various means of hooking a cable to the front of the tractor and using a second tractor to pull it. The most unusual method this author knows of was in England, when LeTourneau Tournapulls were snatch-loaded by a steam traction engine with a cross-mounted underframe winch normally used to shuttle a plow back and forth across a field. Snatch loading became obsolete as more efficient ways of pushloading the scraper from behind evolved.

At first, a simple dozer blade was used, but during the heyday of large scraper operation from the 1940s through 1980s, a number of pushloading attachments were developed.

Dozers were modified by narrowing them to fit behind the scraper so that the blade ends would not waste power by pushing dirt along with the scraper, and by cushioning them so that the tractor could contact the rear of the scraper in motion with less shock impact.

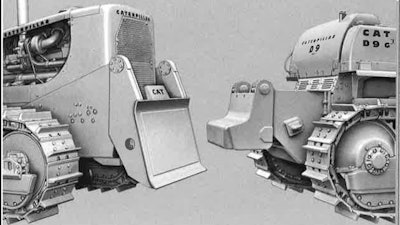

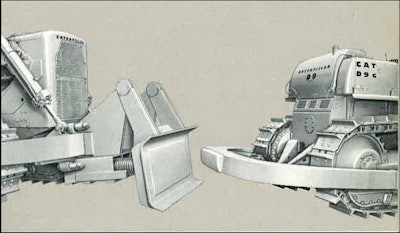

Caterpillar D9G crawler tractors with front (left) and rear C-frames for pushloading. The left-hand machine has a cushion cup; many push cups were simple concave discs.Caterpillar, Inc. sales brochure AE26506, HCEA Archives

Caterpillar D9G crawler tractors with front (left) and rear C-frames for pushloading. The left-hand machine has a cushion cup; many push cups were simple concave discs.Caterpillar, Inc. sales brochure AE26506, HCEA Archives

Other attachments included uncushioned cups and plates, so shaped as to hold the end of the scraper against the center of the attachment thus transmit the most force to it, and cushioned plates and blocks designed with the same logic as cushioned dozers. Plates and cups were mounted either on the front of the tractor frame, or on C-frames that could also mount a dozer blade.

When multiple tractors were needed to push one scraper, attachments such as a cushioned block or a C-frame would be mounted on the back of one or more tractors to give the rear tractor a safe surface to push against. In most cases, two tractors were sufficient, but three or even four pushloaders could be used. Of course, more pushloaders meant more congestion in the cut, all else being equal, as they all repositioned for the next push.

Repositioning quickly and correctly was also a critical part of pushloading, as wasted motion and slow movement meant less time pushing scrapers. In the 1950s and 1960s, some contractors worked around this by having the transmissions in their tractors, mostly older Cat D8s to this writer’s knowledge, reversed so that they had two slow forward speeds for pushing and multiple, faster speeds for repositioning.

There were also some crawler tractors and wheel tractors that were built specifically for pushloading, but those are subjects for another time.