While the truck-mounted crane provided construction cranes with unprecedented mobility when it was developed in 1919, the concept of a self-contained mobile crane that traveled freely on the ground predated it by several years.

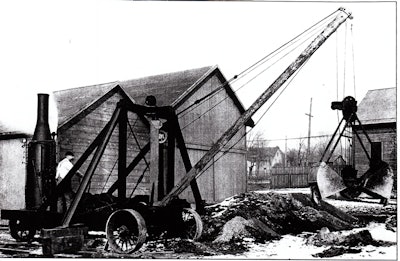

Steam-powered cranes mounted on self-propelled traction wheels were developed as early as 1909, when the John F. Byers Machine Company of Ravenna, OH, was producing its Model 328. This machine consisted of a rigid frame that could be mounted on railroad or traction wheels, and had an upright boiler at one end and a boom, shovel front or skimmer that swung roughly 180 degrees on the other. Byers produced several models of these machines, and by 1919 offered them with gasoline or electric power as well as steam, and with optional crawler tracks under the boom end.

While it was certainly more flexible than a rail-mounted crane, lack of mobility was the main drawback of the traction wheel design; it was slow and not very maneuverable. The truck-mounted crane solved this, but a need remained for a crane that was mobile and free-traveling, but that did not need to travel under its own power at highway speeds.

The exact evolution of the self-propelled, full-revolving crane is not clear. Universal Crane Company, which had developed the first truck-mounted crane, was known to have offered full-revolving cranes on cab-free carriers with steel wheels and solid rubber tires in the early 1920s. Photos of these cranes show no evidence of a visible drivetrain, indicating that they were towed behind trucks. While obviously limited by lack of self-propulsion, these cranes otherwise had the same capabilities as a truck crane but from a smaller footprint.

Eventually, these cranes came to be self-propelled on pneumatic tires. This gave them limited over-the-road capabilities under their own power, although they could not match truck cranes in travel speed. These later self-propelled lattice cranes were rarely used in general construction, but their low travel speed made them well-suited for industrial applications, making lifts in various places of a sprawling plant or refinery.

As truck crane capacity soared past 100 tons in the early 1960s, self-propelled cranes did not keep pace. Self-propelled lattice cranes were phased out in the 1970s and 1980s along with their smaller and mid-sized crawler and truck-mounted counterparts in favor of self-propelled hydraulic cranes.

The Historical Construction Equipment Association (HCEA) is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the history of the construction, dredging and surface mining equipment industries. With over 4,000 members in 25 countries, activities include publication of a quarterly educational magazine, Equipment Echoes; operation of National Construction Equipment Museum and archives in Bowling Green, OH; and hosting an annual working exhibition of restored construction equipment. Individual memberships are $32.00 within the USA and Canada, and $40.00 US elsewhere. HCEA seeks to develop relationships in the equipment manufacturing industry, and offers a college scholarship for engineering students. Information is available at www.hcea.net, by calling 419-352-5616 or e-mailing [email protected].

![Hcm Ax Landcros Press Release[32] jpg](https://img.oemoffhighway.com/mindful/acbm/workspaces/default/uploads/2025/11/hcmaxlandcros-press-release32jpg.mAEgsolr89.jpg?ar=16%3A9&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=135&q=70&w=240)