The 10-year sprint to the near-zero emissions finish line is done. It felt like a marathon but engine, vehicle and equipment makers hardly have time to take a break, because this race is far from over. The next event is a decathlon more than a marathon. Building on the near-zero emissions of particulate matter (PM) and nitrogen oxides (NOx), now we compete to reduce greenhouse gases (GHGs) and continue to improve fuel efficiency, which will require a new bag of tricks.

With the 2010 on-highway vehicle and Tier 4 off-road milestones now mostly in the rearview mirror, a firm pivot has taken place to focus on giving back efficiency and productivity to the customer, and getting used to navigating a world dominated by discussions of low carbon fuels, energy efficiency and lowering GHG emissions.

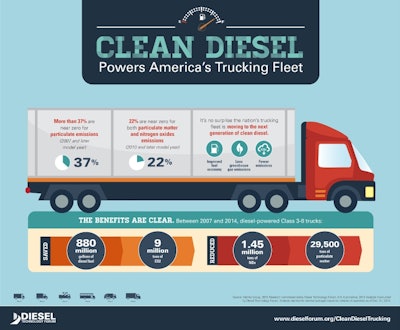

Today, 37% of all diesel medium- and heavy-duty commercial trucks registered in the United States are equipped with newer technology clean diesel engines - those manufactured in Model Year 2007 or newer that have near-zero particulate emissions. And nearly 22% of all diesel trucks in operation are the newest clean diesel technology (2010 and later model year) that are also near-zero emissions in NOx.

So what has this accomplished? Our newest analysis of the benefits of the new technology diesel engines conducted by the Martec Group found the MY2007 or newer Classes 3 to 8 vehicles saved 880 million gallons of diesel fuel, and nine million tons of CO2. In addition, the environmental benefit saw a reduction of 1.45 million tons of NOx and 39,500 tons of particulate matter.

Meeting near-zero emissions for clean diesel was all-consuming and required many compromises and tradeoffs that were not always in favor of the manufacturer or the customer. And now the government is getting into the business of regulating fuel efficiency. Is that a good thing or a bad thing? Let’s revisit that question in about 5 years.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) eased into the world of regulating GHG and fuel economy requirements for medium- and heavy-duty trucks back in 2011. Buyers of new Class 8 diesel trucks in recent years (2010 and newer) are getting 4 to 6% better fuel economy than their previous engine technology—saving fuel means saving money, a motivation to invest in new technology. For heavy-duty trucks, a large part has been due to the use of SCR (selective catalytic reduction) technology that has enabled a more favorable balance of engine-out emissions, fuel consumption and performance.

Some gains have come from implementation of Phase 1 GHG technologies and improvements, as well. Meeting Phase 1 requirements has been mostly an off-the-shelf technology implementation and is generally viewed as a success. But now comes what might turn out to be the 'Summer of Discontent' as the industry reacts to the just-issued Phase II proposed rules which begin in 2018 and go well into 2028. Go to www.oemoffhighway.com/12085950 to download a detailed Fact Sheet on the proposed Phase II GHG emissions standards.

Design and structure of the test procedures, stringency and flexibility are the key vectors in this 1,300-page proposed rule. The proposal would be phased in beginning in 2021 through 2028, and envisions a 26% improvement in fuel efficiency. The rule regulates the total vehicle, including trailer. While there is no industry consensus view on the best regulatory approach, the form of the Phase II standards or their stringency, this rulemaking (that will be finalized in mid-2016) will set the next marathon in motion. This rule has some consideration of alternative fuels like natural gas, however when considering the range of issues regarding methane leaks and negative climate impacts, and the close emissions profile of diesel and natural gas, nothing suggests that any significant shift in fuels is contemplated as a result of this rule.

While everyone is familiar with the failed government investments in solar energy companies, more should know about the success of the SuperTruck program (read more, 10602353 and 11269209). Truck and engine OEMs have had great success over the last 10 years working with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) to squeeze more efficiency out of engines, achieve near-zero emissions, better understand aerodynamics and much more. Many of the fruits of this shared labor are being implemented today on new commercial trucks and demonstrating that an 80,000-pound tractor-trailer can achieve over 12 mpg. But don’t expect SuperTrucks in these concept forms to be on the road anytime soon due to technology, safety and regulatory issues. Head online to www.oemoffhighway.com to read more about Daimler’s concept truck (search 12058508), Navistar’s progress (search 11289264), and Cummins' and Peterbilt’s achievements (search 11313987).

After regulating conventional emissions like NOx and PM from engines since the late 1980s, moving to regulating efficiency via GHG and fuel efficiency mandates in total vehicles raises many new issues. Test procedures, measuring and ensuring compliance in operation of the total vehicle are but a few of the early concerns, while others pit safety against efficiency. Take the case of side mirrors. Using hi-tech cameras instead of the side view mirrors on Class 8 trucks has the potential to yield about 1.5% improvement in fuel efficiency, yet safety regulators have rejected manufacturers' petitions to eliminate the side mirror requirement, even though cameras are proven to be as, or more, effective. This is a place where government would be wise to think and act differently when the case for safety is solid.

In a low carbon emissions world, the focus expands beyond the engine and tailpipe for vehicles on the road or machines on the jobsite. Off-road engine and equipment makers are working to bring efficiency to their customers based on how the machine or engine is used on the jobsite. Technology is coming hard and fast to almost all aspects of life today, and the vehicles that move the economy are no exception.

The use of telematics and GPS-based control systems is moving even faster toward a fully connected worksite, where vehicle location, attachment movement, and overall performance and productivity are measured, monitored and managed on a real-time basis—our industry’s version of Big Data.

Autonomous vehicles already in use in the mining sector are now finding their way to farm fields and construction sites. Truck OEMs have found a plethora of technology such as advanced lane control, adaptive cruise control and radar systems to enhance vehicle safety and driver performance. Daimler Trucks North America even recently received official licensing from Nevada to operate its Freightliner Inspiration fully autonomous commercial truck on an open public highway (read more, 12071407).

The move to renewable and low carbon fuels.

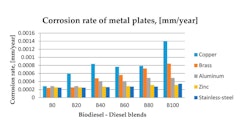

A carbon constrained future demands efficiency in all forms of energy, how it is consumed and the composition of the fuels used; and the future is in low-carbon fuels. The long science experiment and batch production of biodiesel is moving to the next level—at least in California. Expanded use of biodiesel, and particularly second-generation renewable diesel fuels, have high hopes among policymakers for delivering relatively fast reductions in both CO2 emissions and petroleum consumption to all diesel engines and equipment, not just the new generations of technology.

Low carbon fuels are a key provision of Governor Jerry Brown’s announcement in January of this year to reduce petroleum consumption by 50% in California in just 15 years (by 2030). Not only does that seem like an extremely daunting challenge but a possibly unrealistic one, as well. The new challenge accelerates the timeframes by 20 years – from 2050, CARB’s original climate action plan’s full implementation date.

Reducing the fuel consumption and CO2 emissions from diesel engines is influenced by the designs of the vehicles and how they are operated. It is reasonable to expect additional efficiency gains from the diesel engine and entire powertrain. A broader use of hybrid and electric drive systems, as well as development of more powerful and effective energy storage systems will continue to become more prevalent as fuel saving strategies allowing the use of a smaller displacement engine operated in a more steady-state where it is the most efficient and generates the lowest emissions, a strategy that could also reduce the size and complexity of aftertreatment systems.

This October, the EPA will announce its decision on new ozone standards and is expected to reduce the allowable levels of ozone from the current level of 75 ppb down to 70 ppb. The EPA has said that for many of the non-attainment areas, the current federal regulatory programs on vehicle emissions standards and the Clean Power Plan are measures that provide the necessary emissions reduction and largely preclude the need for additional regulatory measures at the state level.

But this hasn’t stopped policymakers in the Ozone Transport Region (DE, DC, MD, PA, NJ, NY, CT, VT, RI, MA, NH, ME) from hinting at their desire to adopt any future ultra-low NOx standard that might be adopted by the California Air Resources Board (CARB) to apply to heavy-duty vehicles in their states.

Herein lies an important issue—as new technology gets more efficient and cleaner, increasingly the major emissions impact comes from the existing fleet. Policymaker solutions only aimed at ratcheting down emissions standards for new equipment another 50% from near-zero will have little impact for decades as the existing-fleet emissions dominate. The largest improvements in emissions from new engine emissions standards have been achieved. Going from essentially unregulated emissions to Tier 2 levels was over a 50% reduction in emissions; but from Tier 3 to Tier 4, less than a 25% reduction.

It’s time to have a more frank policy discussion about efforts that accelerate turnover to new technology. California—leading the charge for lower emissions – could help move out more old equipment and vehicles by changes to the Carl Moyer program to open up incentive opportunities.

All of this is not to say that regulators have lost interest or moved on from conventional emissions standards and future reductions. They haven’t. Discussions are ongoing about a Tier 5 standard – one that would incorporate a particulate number standard along with the mass based standard. There are indications that some regulatory agencies would prefer that all diesel engines had particulate filters even though manufacturers can meet current standards without such devices in some applications; a new particle number standard might be the route to getting that implemented in the U.S.

The weak link in this story of new technology, efficiency and benefits for all is the economy. A less than robust economy means we wait for full-scale adoption of new technology and the benefits to accrue–to show up in measurable terms in air quality emissions models and inventories. Having confidence in sustained economic growth or government action to ignite major economic sparks like long-term infrastructure legislation would surely help.

The Administration has a lot riding on rules to cut CO2 emissions from trucks. Between these and the Tier 3 car fuel economy rules, they make up 20% of the total commitment of CO2 reductions by the U.S. to the Paris International Climate Summit coming up in December. The bulk of the CO2 reductions are attributable to the highly-controversial and already-litigated-once Clean Power Plan.

The success of GHG policy cannot be measured by getting stakeholder consensus on a final rule. It must be measured by its ultimate success in achieving the desired results. Higher costs for vehicles and equipment are guaranteed as a result of fuel efficiency rules. What’s not guaranteed is widespread adoption and purchase of these engines and equipment. Without that, improvements in fuel consumption or lowering of emissions aren’t going to happen.