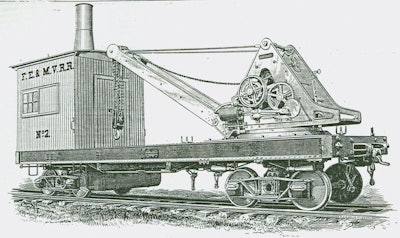

Until 1886, most railroad cranes consisted of a hand-operated pedestal crane on a flatcar, and the few locomotive cranes used in America had been imported from England. That was the year that Industrial Works of Bay City, MI, mounted an improved steam wharf crane on a four-wheeled flatcar for use around its plant. Later that same year, the company introduced the first true locomotive crane to be built in America. This was a 15-ton capacity crane, with the boiler at the opposite end of the frame from a boom that revolved 360 degrees. It was also self-propelled, giving it the ability to move the railroad car it was loading or unloading.

Soon, the locomotive crane resembled the full-revolving crawler crane, in that all of its mechanical and hoisting works were mounted on an enclosed platform that revolved on its carrier. Crane capacity increased over the years; in 1912, Industrial Works’ locomotive crane line ranged from five to 30 tons capacity; in 1923, capacity reached 60 tons. The company's first 30-ton crane was built in 1896, 50-ton in 1899, 100-ton in 1904, 150-ton in 1911, and 200-ton—the world’s largest at the time—in 1922.

Locomotive cranes travelled on four wheels whose axles were attached directly to the crane’s lower frame, or on two four-wheel trucks. Some models were offered on either mount. While more expensive, the eight-wheel crane had several advantages over the four-wheel version: It had greater lifting capacity, it was easier on the track and roadbed, and it could be moved over the road on its own wheels whereas a four-wheel crane could not. The eight-wheeled crane was also more stable, an important factor when working on temporary construction project trackage. Although standard gauge was the norm, locomotive cranes were built to whatever gauge the customer ordered, with the understanding that capacity was directly proportional to track gauge. Eventually, they were also offered on a variety of non-rail mounts.

Locomotive cranes were the only mobile, full-revolving cranes being used in construction at the start of the twentieth century. They could be found on railroad spurs and sidings, loading or unloading equipment, supplies and construction materials. They trundled about large aggregate plants, cement mills and quarries, loading product for delivery by rail, and they clammed aggregates into batch plants situated at trackside for convenient delivery of dry materials. They trod cautiously on lightweight, temporary track and trestles as they handled everything from excavation and pile driving to steel erection and concrete pours at bridges, dams, locks and buildings. By the mid-1930s, locomotive cranes had been displaced from construction applications by more flexible mobile cranes, and other types of lifting equipment replaced them in many industrial and railroad applications in more recent years.

The Historical Construction Equipment Assn. (HCEA) is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the history of the construction, dredging and surface mining equipment industries. With over 4,300 members in 25 countries, activities include operation of National Construction Equipment Museum and archives in Bowling Green, OH; publication of a quarterly magazine, Equipment Echoes, from which this article is adapted; and hosting an annual working exhibition of restored construction equipment.

Individual memberships are $30.00 within the USA and Canada, and $40.00 US elsewhere. HCEA seeks to develop relationships in the equipment manufacturing industry and offers a college scholarship for engineering students. Information is available at www.hcea.net, by calling 419-352-5616 or emailing [email protected].