In one of the tall tales of Paul Bunyan, he and his crew became so productive in harvesting timber that they had to work further and further away from camp, until they reached a point where it took so long to get to the stand being cut that by the time they got there it was time to go back.

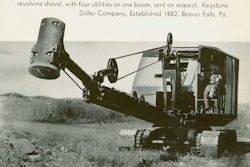

Excavators, both cable and hydraulic, face a similar limitation. They can break out and lift only so much payload at so much length of boom and stick without overbalancing, and the longer the reach to the digging the smaller the bucket’s capacity. Moreover, the bucket’s weight has to be considered; the heavier the bucket, the less weight it can handle beyond a certain distance from the machine’s center of rotation.

Cable draglines provided a way to get around this, because they were capable of digging further away from the machine than could a backhoe. Plus, in theory it could dig as deep as needed. But only so much boom could be safely handled.

It took a while after hydraulic excavators displaced cable excavators before the problem of digging at extraordinary distances from the machine was solved. A larger, heavier excavator could dig further away because of its greater size and counterweighting. But not every job was suitable for the biggest excavators.

The earliest long-reach excavator known to this author is the Priestman line, introduced in England in 1982 to combine the best features of draglines and hydraulic excavators. Its elongated boom was mounted slightly aft of the center of rotation, and a traveling counterweight was mounted to the boom and moved forward and back as the boom and dipper were extended and pulled back, so that it counterbalanced the boom, dipper and bucket. A hydraulically-operated cable winch pulled the bucket in through its digging cycle, and another cable was reeved through a sheave at the pivot between boom and dipper stick. The Priestman excavators had remarkable operating range; for example, the VC20 could handle a 1 cubic yard excavating bucket at ranges of up to 65 feet 6 inches.

Today, many manufacturers of hydraulic excavators offer long-reach excavators, often as variants of standard excavator models. Their buckets are much smaller than those of their conventional counterparts, because of the weight versus reach problem, and they are powered entirely by hydraulic cylinders.

The Historical Construction Equipment Association (HCEA) is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the history of the construction, dredging and surface mining equipment industries. With over 4,000 members in twenty-five countries, our activities include publication of a quarterly educational magazine, Equipment Echoes; operation of National Construction Equipment Museum and archives in Bowling Green, Ohio; and hosting an annual working exhibition of restored construction equipment. Our 2016 show is September 16-18 at our Museum. Individual memberships are $35.00 within the USA and Canada, and $45.00 US elsewhere. We seek to develop relationships in the equipment manufacturing industry, and we offer a college scholarship for engineering and construction management students. Information is available at www.hcea.net, or by calling 419-352-5616 or e-mailing [email protected].