The idea of having major components be interchangeable across different machines makes sense on several levels, especially simplification of maintenance, change-out and parts stocking. It’s a variation of standardization in which a business sticks to as few manufacturers and models of equipment as possible.

An example of standardization in the construction industry is Mangla Dam Contractors. This American joint venture, sponsored by Guy F. Atkinson Company, was awarded the contract to build one of the world’s largest embankment dams in remote western Pakistan in the mid-1960s. To hold down the costs of supporting 47 shovels and cranes, 118 crawler tractors, 30 motor graders, 75 scrapers, 110 haulers and much more in such a remote location, the venture purchased equipment of the fewest brands and models it could so as to keep parts and maintenance costs to a minimum. Almost all major equipment was powered by as few models of Cat and Detroit diesel engines as possible.

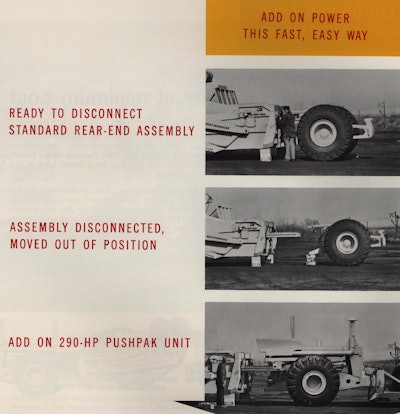

Two equipment manufacturers took notable steps in the early 1960s to incorporate principles of standardization and component interchangeability across different types of machines. One was Allis-Chalmers and the other was LeTourneau-Westinghouse. Both companies explored the same concept – using interchangeable powertrain components on both the tractor and scraper in different combinations for the needs of different applications.  Illustrating the process of changing an unpowered C500 scraper rear end for a Pushpak.LeTourneau-Westinghouse brochure TP470, May 1962

Illustrating the process of changing an unpowered C500 scraper rear end for a Pushpak.LeTourneau-Westinghouse brochure TP470, May 1962

Allis-Chalmers’ 555 tractor and its 44-yd. (40.2 m) 562 scraper were marketed under its Modular Concept. The idea behind this was being able to mix and match components as needed. The owner could use the prime mover by itself to pull other equipment, or yoke two prime movers together to form a 555 tractor. In scraper service, the prime mover could pull one or two scrapers, with or without a power module on the scraper axle. The most successful combination was the single-bowl, powered scraper.

LeTourneau-Westinghouse’s approach was on a smaller scale and didn’t include a push tractor. Its C-500 system consisted of a variant of its famous C prime mover with a Detroit 8V-71 engine, pulling one or two 21 yd. (19.2 m), 24-ton scrapers. One or both scrapers could be equipped with 148 hp (110.4 kW) 4V-71 or 290 hp (216.3 kW) 8V-71 engines. The engine and drive axle assembly for the scraper, called a Pushpak, could be swapped out for an unpowered rear end depending on the job’s needs; the owner simply matched the prime mover to whatever combination of scrapers and the one or two Pushpaks the job required.

Neither product line was a success. Only 74 C500 prime movers and 83 Pushpaks were sold, and many were scrapped after trade-in or recall. Production ended in 1967, and reworked C500s dribbled out of the yard as late as 1969. The 555 was an outright failure, and perhaps a couple of hundred 562s were sold.