By the end of 1922, Robert G. LeTourneau had already achieved two major breakthroughs in scraper design: The first scraper that could be controlled from the towing tractor; and the Mountain Mover, a scraper of far larger capacity than anything else of the time.

These scrapers had one drawback—they had to be pulled by a separate tractor. In his incessant pursuit of a better way to do the job, LeTourneau took scraper design to the next logical level in 1923: self-propulsion.

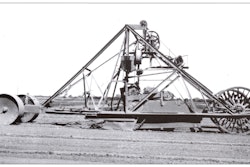

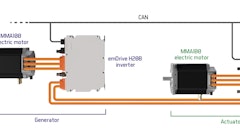

The “Self-Propelled Scraper,” as he called it, rode on four large, smooth, spoked steel wheels. A gasoline engine, transversely mounted ahead of the front axle, turned a dynamo that generated electricity for seven motors placed at points on the machine that required power.

Like the Mountain Mover, it had a 12-yard capacity telescoping scoop. But where the Mountain Mover’s scoop had two sections, the Self-Propelled Scraper’s had five. This author suspects that, given its smooth drive wheels and the operating principles of the two-section bowl, the Self-Propelled Scraper didn’t have the power and traction to load that much material in two sections, so more and smaller sections were needed.

Unfortunately, this remarkable machine had one drawback – its stately 1 mph (1.6 kph) speed. It could move the material, but much slower than tractor-drawn scrapers. After using it on various projects in central California, LeTourneau ended up converting it to a pull scraper and then sold it in 1925.

Even though it was ultimately a failure, the Self-Propelled Scraper was years ahead of its time. It predated modern motor scrapers, also developed by LeTourneau, by 15 years. Its powertrain, with a generator set powering an array of motors at working points of the machine, foretold by 22 years the diesel-electric systems that became LeTourneau’s hallmark. After World War II, LeTourneau committed to this means of powering machinery, and his mammoth LT360, at 360 tons or 216 cubic yards capacity, the largest scraper ever built, had exactly the same power concept as the Self-Propelled Scraper – albeit with 5,080 hp (3,788.2 kW) worth of diesel generators.

The Historical Construction Equipment Association (HCEA) is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the history of the construction, dredging and surface mining equipment industries. With over 3,800 members in over a dozen countries, activities include publication of a quarterly educational magazine, Equipment Echoes, from which this article is adapted; operation of National Construction Equipment Museum and archives in Bowling Green, OH; and hosting an annual working exhibition of restored construction equipment. The 2022 show will be September 16-18 in Bowling Green, OH. Annual individual memberships are $35.00 US within the USA and Canada, and $55.00 US elsewhere. HCEA seeks to develop relationships in the equipment manufacturing industry, and offers a college scholarship for engineering and construction management students. Information is available at www.hcea.net, by calling 419-352-5616 or e-mailing [email protected]. Please reference Dept OEM.