As we have already seen, Robert G. LeTourneau was responsible for several major innovations in scraper design, including the first scraper that could be controlled from the towing tractor, the largest scraper of the early 20th Century, and the first motor scraper. In addition, he was also an early designer of dozer blades for crawler tractors.

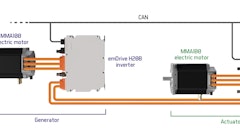

LeTourneau’s early dozers and scrapers were operated by electric motors powered by an onboard generator, and the motors turned winches on the scrapers or a rack-and-pinion mechanism on the dozers. But in the mid 1920s, he found this technology unsatisfactory. Despite its relative convenience and efficiency, the motors were too slow. Something better was needed, and Mr. R. G. once again had the idea.

In 1928, he introduced the Power Control Unit. It was an enclosed winch, driven from the tractor’s rear power take-off. A wire rope was attached to the device being operated, and was wound in or out to control it. A dozer required only a single drum, but the scraper’s complexity made a double-drum unit necessary.

The Power Control Unit and its competitors went on to power other machinery, including “Buggy” positive-ejection bottom dump wagons that slid the body back from the frame to dump; pull rippers; towed cranes; and even shovels, backhoes, draglines and cranes mounted to the tractor. The double-drum unit made it possible to operate two devices, such as a dozer and ripper, and tractors could be equipped with front and rear units to operate both a dozer and scraper.

While positive down pressure was impossible with wire rope control, that disadvantage was more than overcome by faster operation. But that speed increase was not without restrictions. Just as on cable-operated excavators, rope had to be paid out carefully, and if the device being lowered were dropped in free-fall the rope could become snarled or kinked. If the winch was not disengaged, damage could occur as the rope kept pulling the device against resistance. Wire rope also had its own set of maintenance needs to monitor normal wear and damage.

While LeTourneau went on to market Tournarope-branded wire rope, these issues with wire rope led the industry in general to accept hydraulics as that technology became more practical, and LeTourneau to return to electric power in very large ways after World War II.

The Historical Construction Equipment Association (HCEA) is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the history of the construction, dredging and surface mining equipment industries. With over 3,800 members in over a dozen countries, activities include publication of a quarterly educational magazine, Equipment Echoes, from which this article is adapted; operation of National Construction Equipment Museum and archives in Bowling Green, OH; and hosting an annual working exhibition of restored construction equipment. The 2022 show will be September 16-18 in Bowling Green, OH. Annual individual memberships are $35.00 US within the USA and Canada, and $55.00 US elsewhere. HCEA seeks to develop relationships in the equipment manufacturing industry, and offers a college scholarship for engineering and construction management students. Information is available at www.hcea.net, or by calling 419-352-5616 or e-mailing [email protected]. Please reference Dept OEM.