The global energy transition is gathering pace. In 2020, Japan, South Korea, Hungary and China joined Sweden, Denmark, France and the UK in announcing binding commitments to eliminate carbon emissions by the middle of the Century. The EU has announced plans to introduce carbon tariffs on imported products from regions with less stringent environmental rules. The U.S. is set to consider similar measures.

And industry isn’t going to wait to be forced into more sustainable practices by regulation. More than 1250 global businesses have already signed up to the Science Based Targets Initiative, committing to significant reductions in damaging emissions over the coming years. Investors are asking companies in their portfolios to outline their sustainability plans, and banks are offering cheaper loans to companies with strong environment credentials.

In the mobile equipment world, electrification is in full swing, with CO2 reduction only one driver among many. Operators of machines designed for use in urban environments, for example, see the shift away from the internal combustion engine as a way to reduce operating noise and improve local air quality.

So far, however, progress towards fully electric equipment has been patchy. Electric drivetrains are widely accepted in some machine categories, with forklifts the most obvious example. In agriculture, electromechanical actuator (EMA) technology has replaced hydraulics in many applications, with users valuing equipment that provides comfort as well as reliability and easy set up. Eliminating the risk of oil pollution can also be valuable for certain functions in contact with crops. For functions pushing or pulling up to 1 ton, electromechanical systems can cost about the same as their hydraulic counterparts.

Electric drivetrains have become the standard in forklift trucks used indoors or in warehouses. To improve runtime, the efficiency of its work or steering functions can be improved by employing electromechanic actuators, such as the Ewellix CASM-100.Ewellix

Electric drivetrains have become the standard in forklift trucks used indoors or in warehouses. To improve runtime, the efficiency of its work or steering functions can be improved by employing electromechanic actuators, such as the Ewellix CASM-100.Ewellix

Ready for the heavy lifting

When it comes to high-power applications, however, progress on electrification has been slow. OEMs worried that they would not be able to find suitable electromechanical solutions for demanding tasks, or that electromechanical technology would be too expensive or too technically challenging.

It could be time to re-visit those assumptions. Recent developments in motor and battery technologies are making battery-electric vehicle (BEV) technology viable for a much wider range of mobile machines. And in BEV applications, EMA systems offer some compelling advantages over hydraulics, even for demanding work functions.

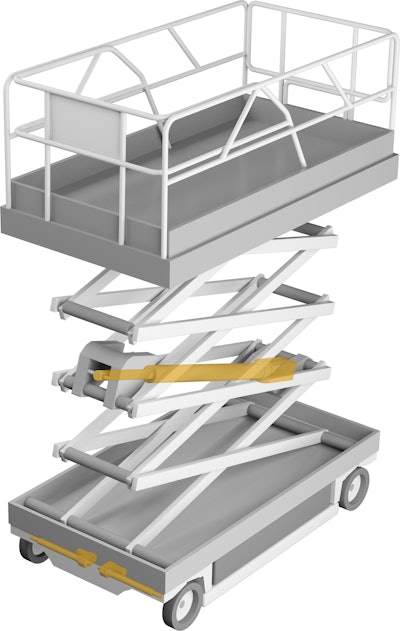

High-performance electromechanical linear actuators (EMA) replace a conventional hydraulic cylinder with a ball screw drive, coupled to an electric motor and gearbox. The resulting unit is compact, rigid and capable of delivering high forces and extremely accurate position control. Even force impact and vibration concerns can be overcome with innovative shock absorption systems.

The first big benefit is efficiency. An EMA converts battery power into useful work much more efficiently than an electro-hydraulic system. Additionally, EMA systems can recuperate potential energy when back-driving, feeding valuable power back into the battery. Advanced lithium-ion batteries can absorb high rates of charge too, making the most of this capability. Together, these characteristics can reduce overall energy consumption by as much as 50%, enabling longer runtimes or a significantly smaller, cheaper and faster charging battery.

Ewellix CAHB22E linear actuators are suitable maintenance-free replacements for pneumatic or light hydraulic cylinders with 32mm or 40 mm bore holes in medium-duty cycle applications. Rated IP66M/69K (and sealed by a vent) the self locking actuators deliver push forces to 10,000 N and pull forces to 20,000 N.Ewellix

Ewellix CAHB22E linear actuators are suitable maintenance-free replacements for pneumatic or light hydraulic cylinders with 32mm or 40 mm bore holes in medium-duty cycle applications. Rated IP66M/69K (and sealed by a vent) the self locking actuators deliver push forces to 10,000 N and pull forces to 20,000 N.Ewellix

Then there’s maintenance and reliability. EMA systems provide oil-free operation. That eliminates the risk of leaks, which hit productivity and can lead to costly penalties in sensitive work environments. Compared to hydraulics, electromechanical systems need very little routine maintenance, with no need for regular inspections and seal replacements. That means lower costs for operators, and less unproductive downtime.

If something does go wrong, replacing an EMA is a simple plug-and-play operation. That means machines can often be fixed onsite, with no need for specialist skills and tools, no oil to drain or refill, and no time-consuming recommission or recalibration.

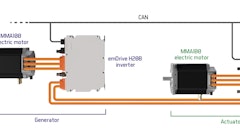

Modern EMAs can incorporate smart functionality, enabling various productivity benefits. The speed, position and acceleration of electromechanical actuators can be precisely controlled over their full range of motion, without the need for elaborate additional control equipment. That capability drives up machine performance and is a critical enabler for new generations of smart machines designed for a wider range of tasks and operating conditions, or which adapt their behavior dynamically under computer control. The communication between electromechanical actuators and the electronic control unit of the equipment uses simple input/output wires or communication like CANBus. That greatly simplifies machine design and assembly, without the need to incorporate bulky hydraulic reservoirs, complex control valves or oil-filled tubing.

Electromechanical actuators are also ready for the industrial Internet of Things (IoT). While collecting performance and reliability data from hydraulic or pneumatic systems requires complex additional sensors, electromechanical systems offer machine manufacturers and operators straightforward access to high-quality data, suitable for fleet monitoring applications or as the basis for predictive and condition-based maintenance approaches through a telematics integration.

Taking a TCO approach

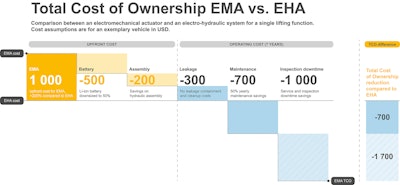

In high-power applications, the upfront cost of each EMA is still higher than an equivalent hydraulic cylinder, although those costs are dropping as increasing adoption drives economies of scale. To make a more realistic comparison between the two technologies, however, it is essential to consider the total cost of ownership (TCO) of the complete system. The exhibit below is a representative TCO analysis for one mobile BEV. It shows the cost differences between an EMA and a hydraulic solution across the whole system and the full machine lifecycle. In this case, 80% of the additional upfront cost of the EMA system is saved by the machine OEM through a reduction in battery cost and simplified assembly. For the owner, a slightly more expensive machine more than pays for itself with lower maintenance requirements, no leakage costs and significantly higher availability.

Ewellix

Ewellix

Designing for EMA

When evaluating the switch from hydraulics to EMA, machine designers should keep a number of important factors in mind. First, what are the drivers for electrification? This could be reduced energy consumption, higher performance, or easier installation, for example. Which machine functions provide the best return against these criteria?

For the chosen functions, what loads and speeds are involved? That isn’t always obvious, since designers used to working with fluid power systems often err on the side of caution, installing oversize cylinders “just in case.” With an EMA, ensuring a good match between the actuator and its task can have a big impact on costs. Likewise, it is important to consider the duty cycle of the function. Actuators that move infrequently can use smaller, less costly motors than those in continuous operation.

Beyond these basic specifications, what are the other key operating requirements? Will the machine need to cope with high vibration levels, impact loads, or difficult environmental conditions? Is minimizing noise a priority? These factors may impact the choice of actuator and its configuration. Modern EMAs often use a modular design, allowing the characteristics of each actuator to be fine-tuned to suit its application, while still providing OEMs with a cost-effective, comprehensively tested and proven solution.

Ewellix’s CASM-100 modular electric cylinder platform is a line of modular (customizable) actuators developed to address a wide range of heavy machinery applications. Several options are available, making CASM-100 actuators suitable replacements for hydraulics on high-load axes — even those needing up to eight tons of force over medium to high duty cycles.Ewellix

Ewellix’s CASM-100 modular electric cylinder platform is a line of modular (customizable) actuators developed to address a wide range of heavy machinery applications. Several options are available, making CASM-100 actuators suitable replacements for hydraulics on high-load axes — even those needing up to eight tons of force over medium to high duty cycles.Ewellix

How will the new actuators be integrated into the machine? EMAs are not like-for-like replacements for hydraulic actuators and the designer will need to consider the space required for the actuator body, its motor, and the routing of cables. At the same time, replacing a hydraulic system may create opportunities to better utilize space elsewhere, since there will be no requirement for an oil reservoir or bulky hoses.

What motor voltage and technology should be used? This depends on the available power on the vehicle (low voltage or high voltage, AC or DC) and the efficiency and performance considerations. While brushed DC motors are lower cost options, limitations in lifetime and efficiency could render them more costly in the long run compared to AC induction or permanent magnet motors.

Can the machine design or specifications be altered to take advantage of the superior performance characteristics of the new actuators? EMAs have better positioning capability, motion control and feedback, and are able to drive loads in push and pull direction. That could pave the way for design simplification, or the inclusion of value-added functionalities.  Ewellix electromechanical actuators can be used in applications requiring oil-free operation or demanding higher energy efficiency, with added benefits of integrated sensors and telematics connectivity.Ewellix

Ewellix electromechanical actuators can be used in applications requiring oil-free operation or demanding higher energy efficiency, with added benefits of integrated sensors and telematics connectivity.Ewellix

In most cases, a first step into the world of electromechanical power is easiest on systems with a small number of hydraulic cylinders. This keeps the design overhead low, while eliminating the entire hydraulic system maximizes the benefits for both OEM and end user. That said, Ewellix has worked on a number of successful hybrid applications that combine hydraulic and electromechanical power for different functions on the same machine. Finally, whatever the application, it always pays to talk to the experts. EMA system manufacturers are passionate about the technology, and always willing to help customers work through the key design decisions.

Modern EMA technology gives OEMs the tools they need to ensure a smooth transition to a world of fully-electric mobile equipment. That transition doesn’t have to be a compromise; tomorrow’s electric machines will be smarter, more reliable, more capable, and more cost effective than their predecessors.

This article was written and contributed by Thomas Lotz, Director Mobile Machinery at Ewellix.

About the Author

Thomas Lotz is Director of Mobile Machinery at Ewellix. He has experience in R&D, business development and product management. Lotz holds a PhD and Masters in Mechanical Engineering.