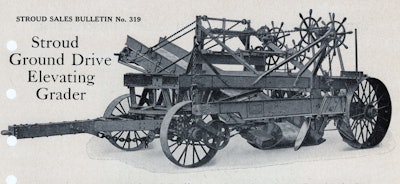

Working from a sales training manual published by Stroud Road Machinery Company of Omaha, Nebraska, in 1931, let’s begin a detailed look at elevating graders.

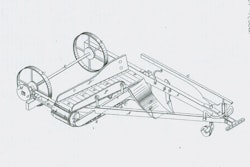

An elevating grader’s digging and loading assembly, consisting of the plow, conveyor and related components, could weigh 2 or 3 tons, and it bore tremendous load strain for 10 hours or more a day, six days a week. The elevating grader’s frame had to be both strong and somewhat flexible, and it had to have ample clearance above the conveyor belt while allowing the operator a good view of the work.

Dirt had to be cast far enough from the cut to enter a hauler being loaded, or windrowed clear of the grader. The conveyor’s length had more bearing than its speed on the cast, and could be ordered in longer or shorter lengths depending on need. Longer conveyors required counterweights. An extension chute could be used instead of a longer conveyor, but Stroud found it inferior to length. The conveyor rollers were wooden cylinders. But they were prone to “weather-checking,” or splitting in extremes of high and low humidity. The roller could still be used unless the crack was severe, but could crack even when brand new. This was considered a normal operating expense, except by finicky customers who made warranty claims that Stroud usually could not honor because the roller had no demonstrable flaws.

Stroud put metal bands on the ends of its rollers to avoid cracking, but they fell off if the wood shrank. Steel rollers were tried unsuccessfully, and the apparent solution was rollers made of extra select air-dried gumwood, with self-aligning pins and clamped-on end caps in place of bands.

The conveyor belt could handle up to a couple hundred-thousand cubic yards of good material before wearing out. Abrasive materials were rough on it, and rocks and large unbroken chunks would also accelerate wear by riding up it and rolling back down repeatedly. More often than wearing out, the belt could be damaged by snags and tears from jammed rocks, and this was another assumed operating expense. The belt needed to be kept at proper tension for most efficient operation. There were different ways of doing this. Stroud considered the most effective to be set screws on the upper (drive) drum, while moving the base of the conveyor accordingly. If the belt had stretched beyond the range of these adjustments, either it had to be shortened or its frame extended.

Spillage from the conveyor needed to be cleared from its base to prevent clogs and damage. Again, there were various approaches to this; Stroud chose a mechanism operated by lever from the operator’s platform. A competitor, the Austin Machinery Company, used an auger that tended to clog, freeze up or wear through its plating and damage the belt; but customers accepted it, and Stroud derided the design by saying, “a man buying an Austin machine is very frequently buying a cathole cleaner and not an elevating grader.”

Interestingly, similar clogging problems plagued the much larger Euclid BV series belt loaders that rendered these elevating graders obsolete.

Thomas Berry is an archivist and editor with the Historical Construction Equipment Association (HCEA).