Heavy equipment manufacturers typically deal with large, complex, highly engineered products with high work content that is measured in hours, days, weeks or even months. These companies are not like automotive manufacturers that produce a repeatable product in minutes or seconds. Consequently, applying continuous improvement techniques from the automotive industry like lean is not straightforward. However, options for applying lean techniques to heavy equipment build exist that will not only improve efficiency, but also add to top-line business growth.

The destination of Operational Excellence

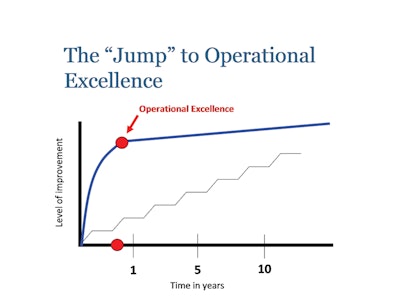

Lean taught practitioners seek out and eliminate waste through the use of tools such as 5S, Kaizen, Poka-Yoke (mistake proofing), Total Production Maintenance (TPM), visual systems, setup reduction, quality in process, standard work and more. Using these tools, an organization finds an area of the operation that needs improvement, attacks it, improves it, then sustains the improvement. The organization then finds the next area to improve, and repeats this process endlessly, resulting in a journey that yields incremental improvements in efficiency year after year if all goes well. (See Graph 1 for a visualization of continuous improvement through incremental changes and implementation.)

However, a new understanding of lean is providing significant gains in productivity and top-line business performance as well – in months, not years, even in the heavy equipment build industry. The idea is that lean is not an endless journey without a destination (as originally taught), but has a destination. And that destination is Operational Excellence.

To arrive at the destination of Operational Excellence, manufacturers follow a process. (See Graph 2 for a comparative visualization of Operational Excellence versus Continuous Improvement seen in Graph 1.) The first step is to define clearly where the improvement is going and what the organization is trying to achieve so employees at every level know what their respective work environments would look like when they arrive. And a practical, hands-on definition is the definition of Operational Excellence, which is when “Each and every employee can see the flow of value to the customer, and fix that flow before it breaks down.”

The importance of self-healing flow

To be successful in an industry that builds highly complex products over very long cycle times, it is critical to understand the application of lean concepts that drive Operational Excellence, the foremost of which is: Operational Excellence is not about eliminating waste. Instead, it is about creating a lean value stream flow from raw material to the customer.

But it is not just any flow; it is a “self-healing” flow, or flow that can be fixed without the intervention of management. This means that the employees in the flow are able to visually distinguish normal flow from abnormal flow and correct abnormal flow on their own before it becomes catastrophic and disrupts the flow of product to the customer. While traditional lean thinking teaches that creating flow is a method to eliminate waste, in Operational Excellence, organizations strive to create flow simply so they can see when flow stops.

And there is an “acid test” to see if Operational Excellence has been achieved. It’s simple: just bring a visitor in to the operation, have them walk through it, and then ask, “Can you tell if we are on time to our customer needs right now?” If the visitor cannot, then the operation has not yet arrived at its destination.

The eight principles of OpEx

While lean relies on a “change agent” or strong leadership or management to drive it, Operational Excellence follows a process that provides the design and implementation methods. Operational Excellence can be achieved by following eight principles that should be done in sequence, and each principle may have many guidelines within it. In short, it is a recipe that can be adapted to many different production environments, including those faced by heavy equipment manufacturers.

The eight basic principles of Operational Excellence are as follows[3]:

- Design lean value streams

- Make lean value streams flow

- Make flow visual

- Create standard work for flow

- Make abnormal flow visual

- Create standard work for abnormal flow

- Have employees in the flow improve the flow

- Perform offense activities

The first principle – design lean value streams – is where heavy equipment manufacturers can modify traditional lean techniques to be successful in their complex environments. In this step, rather than having a team map out the current state and then brainstorm or kaizen out waste, which is the typical approach, value stream flow is designed using guidelines.

The eight guidelines for designing value stream flow are as follows: [4]

- Takt: The rate of customer demand

- Finished goods strategy: How the factory will know what to build next for a given value stream

- Continuous flow: A method of production that produces parts in a make-one, move-one fashion

- FIFO: A method of production between disconnected processes that makes parts first in, first out

- Pull: A method of production between disconnected processes where a fixed amount of inventory is held and consumed on an as-needed basis

- Single point scheduling: The one process in the value stream to which the production schedule is issued, identified as where flow stops and pull begins

- Interval: How long it takes the pacemaker process to cycle through each part in a given product family

- Pitch: The management timeframe, or how often completed parts are taken away from the pacemaker process

Adapting design for heavy equipment

Many of these guidelines can be adapted to address the unique environments of heavy equipment build. For example, consider the concept of “Pitch.” Pitch teaches organizations to create a timeframe so everyone (not just management) will know if the flow of the product is on time to customer demand. It is usually done by multiplying takt time by a physical quantity such as a case pack. For example, the result of multiplying takt time (say two minutes) by the pack quantity (say 10 per case) is that the operation should produce a case every 20 minutes in order to meet customer demand. Once established, the material handler would be told to pick up a case every 20 minutes. If the material handler cannot pick up a case every 20 minutes, there is a problem, and everyone knows it.

However, in heavy equipment build, the application of Pitch in the traditional method simply will not work. With such long takt times, and no “case quantity,” it could be days or weeks before the operation knows if it is on time. Therefore, this guideline would be adapted by modifying it to inverse pitch, which is used when products have long takt times. With inverse pitch (meaning pitch time is shorter than takt times) the long takt time build would be broken up into four-hour increments. Each four hours, parts would be presented in a kit, each kit taking four hours to assemble. If a kit is not consumed in four hours and parts still remain, the operation knows it is not on time, which is the purpose of Pitch.

Another technique for heavy equipment is creating a “Master Pitch” by sequencing crane moves. Similar to a flight leaving an airport at a preset time, preset times would be established when the crane would move heavy parts through the shop – creating a normal flow for the product build. By creating and defining normal flow, the operation can also see abnormal flow. Once it can see abnormal flow, the employees working in the flow can be taught methods to correct it without management intervention – achieving the destination of Operational Excellence.

The result? Business growth

Enabling the employees to fix the flow before it breaks down means management is then freed up to spend its time working on something very valuable to future growth, which is to work on offense, or the activities that grow the top line of the business. Offense activities might entail working on new product development, spending more time with Operations upfront in the innovation funnel to better design products for manufacturability, working more closely with existing customers and meeting with potential ones, becoming a solution or service provider rather than a part supplier, or anything else that might grow the business in either the short- or long-term.

The key is to create the ability to innovate with the customer. To do this, organizations must first earn that right by delivering product seamlessly to the customer, with no interruptions. That means the customer places an order, the operation produces the order, and the order is shipped, without any stress or worries. Factories – even ones producing large products with high work content and long takt times – run like this for one simple reason: they were designed to do so using the principles and guidelines of Operational Excellence.

Once this state is achieved, the organization can then begin to talk to the customer about how they use its product and create solutions they want now and in the future. The result? An operation that is designed to support the top-line business growth of the company.

[3] Duggan, Kevin J., Design for Operational Excellence: A Breakthrough Strategy for Business Growth (New York, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011), 123.

[4] Rother, Mike and John Shook. Learning to See. The Lean Enterprise Institute. Cambridge, MA. 2003.