Thomas Dill of Bay City, MI, was awarded at least three patents for his improved steam shovel. On May 4, 1880, U.S. patent #227222 was issued for a hinged dipper and sliding dipper stick that allowed the dipper to be tilted by a steam piston for optimum digging or dumping, and for a tilting boom for the shovel. Additional patents were issued in July of 1881 to Mr. Dill for steam-operated swing and leveling jacks, among other features.

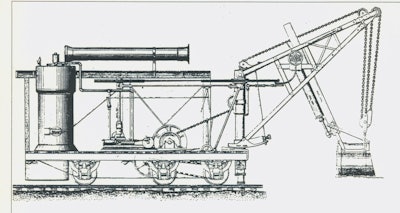

The Dill’s Steam Shovel and Derrick Car was mounted on six railroad wheels, and the middle axle was machined to allow lateral motion when negotiating extremely tight curves. It could travel at eight to 10 miles per hour by means of a spur pinion and drive chain from the engine shaft to the front axle. The dipper's capacity was approximately one to two cubic yards.

More significantly, the Dill's Steam Shovel was apparently the first standard-gauge railroad shovel. Industrial Works had been founded in Bay City, MI, in 1873 to produce boilers and sawmill equipment, and the only available railroad shovels at the time worked from wide-gauge track. George Kimball, the firm’s first president, returned to his former career in railroading following the Panic of 1873, and in his new position he approached Industrial Works in 1880 about building a standard-gauge railroad shovel that would simplify its operation and movement. Dill had assigned his patents to a principal of Industrial Works the same year, and the coincidence suggests that the Dill Shovel—which was renamed the Clement Shovel— fulfilled Kimball’s request.

The Clement Shovel proved a failure. Its crowd and swing employed very long steam cylinders to apply their motion; the eight-foot stroke crowd cylinder was directly connected to and moved with the dipper handle, thereby subjecting it to numerous stresses and strains. But the experience gave Industrial Works an entry into the railroad crane market, and it went on to be a leading producer of locomotive cranes and railroad wreckers. It returned with limited success to shovel manufacturing in the 1920s with a line of crawler machines that was discontinued by successor Industrial Brownhoist by the 1950s.

This article is adapted from an article in the current issue of Equipment Echoes, the quarterly magazine of the Historical Construction Equipment Assn. (HCEA). The HCEA is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the history of the construction, dredging and surface mining equipment industries. With over 4,300 members in 25 countries, its activities include operation of National Construction Equipment Museum and archives in Bowling Green, OH, and hosting an annual working exhibition of restored construction equipment. Individual memberships are $30.00 within the USA and Canada, and $40.00 US elsewhere. The HCEA seeks to develop relationships in the equipment manufacturing industry and offers a college scholarship for engineering students. Information is available at www.hcea.net, by calling 419-352-5616 or e-mailing [email protected].